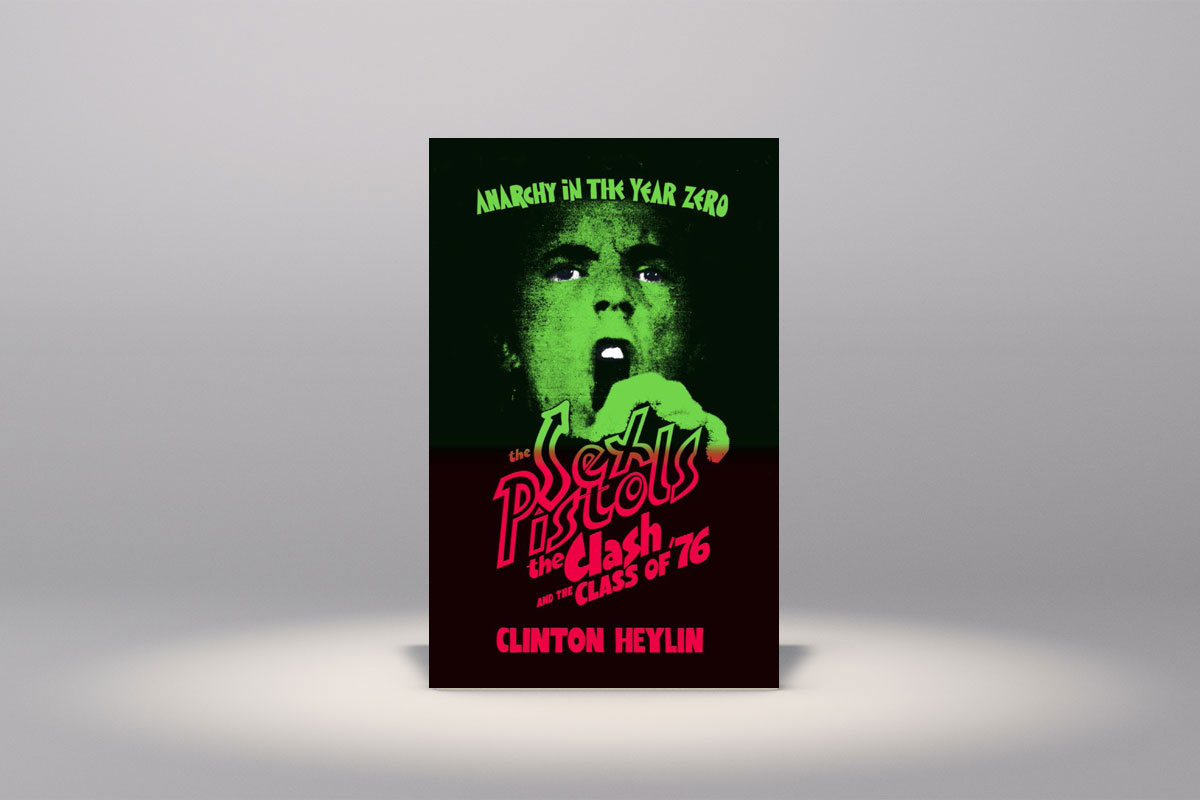

An extract from Anarchy in the Yeat Zero.

Whatever Rotten’s concerns about the original trio’s musical chops, McLaren knew that his presence gave renewed purpose to his own great plan. Starting the third week of September 1975, he agreed to rent the band a rehearsal room and studio flat behind Zeno’s bookshop, having answered an ad in Melody Maker which began, ‘Tin Pan Alley. Must be useful for some musicians, agents or such…’ His hero, fifties impresario Larry Parnes, would have been proud of him.

(Later on, McLaren would begin to parrot Lydon, asserting that ‘the music wasn’t [ever] important. It was just a declaration of intent and an attitude.’ But such post-Pistols statements are belied by his every action in the year the Pistols mattered.)

Having spent months looking for grade-A Attitude, McLaren had stumbled on someone it spumed from like some great geyser. Once Rotten found a ‘way of expressing it’, bile gushed forth in all the lyrics he wrote in the months before the band found a public platform for this loaded Pistol. The songs had titles like ‘Submission’, ‘I’m A Lazy Sod’ and ‘We’re Pretty Vacant’, to which Matlock, Cook and Jones set their own Small Faces-but-for-the-seventies sensibility. McLaren couldn’t wait to tell one former incumbent:

Nick Kent: The first time Lydon’s presence was made known to me was when McLaren and I were walking down Denmark Street, and he turned to me and said, ‘We’ve found a singer. He’s the best thing in the group. He looks like a spastic, and he’s just written this song, “You’re only twenty-nine/ You got a lot to learn.”’ [‘Seventeen’]

As for Rotten, he couldn’t wait to unveil his own version of punk rock on a London that still hadn’t quite recovered from the Blitz. Years of being ignored, put down and put upon had produced a genuinely angry young man who, like an automaton of hate, one only needed to wind up (and stand back) to see folk scatter. Unless one felt just like him. And Rotten now had a remit, planted there by the equally iconoclastic McLaren:

Johnny Rotten: We didn’t stay in a rehearsal studio until we were so perfect we were boring. The whole idea was to get out and have some fun … and we hoped that some people would see us and go away and form their own bands. We wanted to make a new scene. [1977]

The ‘we’ in question was not the royal ‘we’. Rather, it represented the philosophical union of manager and man-at-the-mike which would last until the darling buds of May, that is, the first flickers of infamy. For now both were equally anxious to smelt the Sex Pistols in the furnace of public opinion and see if it still stood up. But neither of them had a clue as to how one actually secured gigs. McLaren’s last resort was literally called The Last Resort, a late-night restaurant/club on the Fulham Road, which agreed to allow them to play, then at the last minute changed its mind.

When this potential avenue fell through, the Pistol with the greatest pop sensibility, Glen Matlock, took matters into his own hands. He convinced the social secretary at the art college he was ostensibly attending – thus receiving an annual government hand-out without having to ‘sign on the social’ – to let them play. St Martin’s College of Art had several things going for it. It was not only slap-dab in the heart of the city, it was across the road from their new rehearsal room. Most importantly, it was not a pub.

All it took was Matlock’s request. There were many tin-pot colleges in the South East that needed bands willing – for ‘beer money’ at best – to provide support for an evening’s entertainment in front of apathetic students pissing away their grant at the subsidised bar of a weekend. When there were no Christians available, even a band calling itself the Sex Pistols would do. The bassist promptly decided to visit other art colleges in the environs to see if it was just as easy to get gigs elsewhere:

Glen Matlock: Just before that [St Martin’s] gig, I went over to Central School of Art in Holborn and swung us another gig there … ‘I’m in a band and we’re looking for a gig.’ ‘What’s the name of the group?’ asked [social secretary] Al [McDowell]. ‘The Sex Pistols.’ [His friend] Sebastian [Conran]’s eyes lit right up … ‘With a name like the Sex Pistols, we must have you.’ So I invited them to the gig at St Martin’s.

This meant at least two people would be there to see the Sex Pistols – as opposed to the headliner, Bazooka Joe. However, if Matlock was relying on the band’s manager to fill out the sparse throng from his address book of contacts, he was to be disappointed. McLaren wasn’t yet sure they were ready. The extent to which he drummed up interest was mentioning it to the fashion-conscious boy and girl who ran Sex, Gene Krell and Jordan, and its accountant, Andy Czezowski, a colourful character but hardly a music buff.

On the night, though, McLaren was a most willing rabble-rouser. Bazooka Joe’s bassist well remembers at the soundcheck, ‘Malcolm standing at the front, orchestrating them, telling them where to stand.’ When they did start playing, at ear-splitting volume, Krell, who was standing alongside his boss, remembers, ‘Malcolm looking perplexed and then curious. I think he could see what a lot of the clued-up amongst us could see – this raw talent.’

If so, he had a musical antenna like few others. The drummer pounding away at the back of the stage is not so convinced it was ‘raw talent’ McLaren heard, and not the sound of a penny dropping: ‘I don’t know what he thought about the music … but he did know we were able to shock, … and I think he [then] made a decision to get more involved.’

At the time, McLaren was as likely as the band to draw others’ attention. St Martin’s attendee Paul Madden, for one, noticed some ‘weird bloke … wearing peg-leg trousers … [who] kept running back and forth’, and formed the view, ‘He was trying to start trouble.’

He need not have bothered. When it came to looking for trouble, the mere presence of the Pistols would more than suffice. And St Martin’s was the living proof. As Madden told punk chronicler John Robb, ‘They had an attitude that was basically, “Fuck off, we’re the Sex Pistols.” … They had a confidence in what they were doing.’ Even from the makeshift stage the band could see that they had set something in motion as yet unnameable – but explosive:

Steve Jones: We’d start[ed] playing live shows before we could play, really. I mean, we could make noise and some sort of construction of the songs and stuff; but it was madness, it was total madness.

John Lydon: The college audience had never seen anything like it. They couldn’t connect with where we were coming from, because our stance was so anti-pop, so anti-everything that had gone on before.

Paul Cook: We went on and it was really loud. It was deafening. And we were going really mad, ’cause this was our first gig and we was all really nervous. And suddenly you had this great big hand pop out, and someone pulled the plug out. [1977]

That someone, possibly chewing gum, was in the employ of Bazooka Joe, whose drummer John ‘Eddie’ Edwards had stuck around long enough to see Rotten ‘get up and sing in his torn woolly, [before] everyone said, “Oh, they’re not much good, are they?” and went and sat in the bar … [We just thought] they were a bit untogether and a bit messy.’

Bazooka didn’t stay in the bar for long. By this time the Mandrax Jones had popped shortly before hitting the stage was beginning to kick in and, as the boy looked at Johnny, he began to think, ‘This is fucking fantastic … I’ve made it. We’re actually playing in a band.’ (By his own admission, he ‘was fucked up’.) Jones started to get a bit carried away, turning his amp up full and aiming swipes at the PA the headliners had never been entirely happy sharing, sending a Bazooka Joe roadie scuttling across the road to the pub where the band had settled:

Robin Chapekar: We were sat in the pub and one of our roadies came running in, shouting, ‘You’d better get back! They’re trashing the gear and everyone is leaving in droves.’ We shot back. They were making a massive noise … They were kicking the amps, the drummer was trashing the drums. We went over and said, ‘Enough is enough!’ Danny took the mike off John and I took the amp off Steve and pulled the plug on him … They were too loud and the space wasn’t big enough.

Not every member of Bazooka Joe shared the general distaste. In this particular boot camp, bassist Stuart Goddard comprised a minority of one, ‘The rest of my band hated them … They thought they couldn’t play … I thought they were very tight.’ But even he had to admit, ‘They were abusing the instruments.’ The abuse didn’t stop there. When the plug got pulled, there was either ‘a brawl’ (Chapekar), ‘a bit of a fracas’ (Matlock), or ‘a huge scrap’ (sayeth Lydon).

Predictably, the cause was Rotten who, according to Goddard, ‘slagged off Bazooka Joe … [so] our guitarist Danny Kleinman leapt from the front row and pinned John against the back wall.’ So much for inter-band camaraderie. For Goddard, it would prove a turning point, ‘I came out of that gig thinking, I’m tired of Bazooka Joe, I’m tired of Teddy boys.’ (It would still take several top-up doses of the Pistols in performance for Adam Ant to emerge from Goddard’s febrile imagination.)

Matlock convinced himself the evening’s events had put the kibosh on the following night’s Central School of Art gig. To his mind, the whole performance had come across as ‘something of a racket. Plus, Bazooka Joe kept on pulling the plugs on us, trying to get us off the stage … [But Al McDowell] kept roaring with laughter all the way through the set – well, what we managed to do of it. I really thought we’d blown it … In fact, he really liked us.’

The following night they succeeded in getting the whole way through their eleven-song set. Indeed, Matlock would subsequently insist the Central was ‘one of the best gigs we [ever] did’. And the reaction was largely positive, aided as it was by a few familiar faces. As Steve Jones observes, ‘They pulled the plug on us [at St Martin’s], but the next gig, all the [same] crowd was there again.’

McLaren immediately realized art colleges were the best way to acquire valuable stage-time and hone the Pistols’ performance-art, while distancing the band from the current pub-rock revival which, to McLaren’s mind, was giving ‘rock revivals’ a bad name.