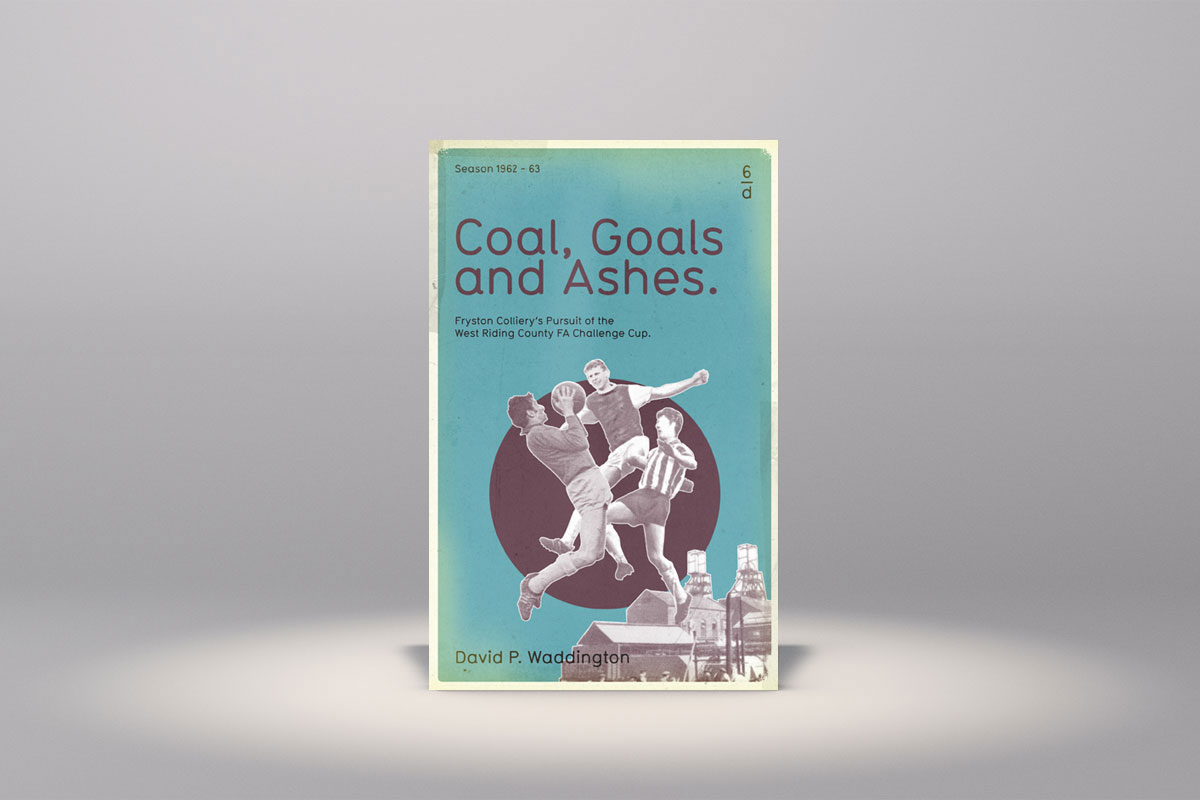

In this extract from the intro to Coal, Goals and Ashes, David Waddington outlines why a professor would spend his free time writing a book about a colliery football team.

Wednesday, 22 May 2013 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the day that Fryston Colliery Welfare, then a humble Second Division team in the West Yorkshire League, took on the seemingly invincible Bradford side, Thackley AFC, in the 1963 West Riding County Football Association Challenge Cup final (WRCC Cup). Throughout most of the twentieth century, the WRCC Cup was justifiably regarded as the local equivalent of the FA Cup – the ‘ultimate prize’ – for amateur teams in the Castleford area. This book utilises newspaper archives and interviews with the players of both sides to explain the full emotional, cultural and historical nature and significance of their famous encounter.

My main motive for writing this book is unashamedly personal: my father, Peter (Pete) Waddington, was captain of the Fryston team that played against Thackley in 1963, and also in the ‘return match’ between the two sides at the equivalent stage of the following year’s competition. I had first considered the possibility of writing a commemorative publication as early as 1985 whilst in the process of researching my earlier book, One Road In, One Road Out: A People’s History of Fryston, but the project then lay dormant until an article appearing in the Pontefract and Castleford Express (hereafter, referred to as the Express) proved both captivating and inspirational. The piece in question centred on a photograph of the 1963 team, sent in by a reader, the Castleford-born David Nathan, and an accompanying letter in which he outlined the qualities of a set of players he had clearly idolised when just a boy:

The goalkeeper Archie Ward was brilliant and would have made David Seaman look ordinary... The defence was rock solid with iron man Brian Wood, Johnny Appleyard and Agga Mattinson [sic]. Jack Sharpe [sic], a man of small stature but huge heart, inspired the team and was the toughest of competitors. The captain was Pete Waddington, a tough but classy midfielder, and the engine room of the team. Terry Templeman was known as perpetual motion, had a shot like Eusebio and covered every blade of grass. Up front were Fred Howard, stylish Cliff Braund and goal-scoring left-winger Trevor Ward. There was also the George Best-type right-winger, Barry Robinson, the team pin-up. Collectively they were Castleford’s best ever football team.

My reaction was instantaneous. I asked my dad to compile a list of the contact details of all his former Fryston team-mates. He and my daughter, Laura, then helped me obtain photocopies of all of Fryston’s 1962-63 season’s match reports from the Express archives, which exist on microfilm in the Pontefract Library. However, this early momentum soon stalled as it became apparent that things were likely to prove far more difficult than first imagined. I already knew, for example, that two players from the 1963 team (Johnny Appleyard and Freddie Howard) had since died. I was then told that Cliff Braund and Archie Ward had emigrated, to New Zealand and Australia respectively, and that no-one quite knew the whereabouts of Barry ‘Cobbo’ Robinson, who was understood to have opened a chip shop ‘somewhere out in Bradford’. To crown it all, for some reason Trevor Ward never seemed willing or able to answer his phone. The growing feeling that there were far too many potential obstacles to overcome was compounded when I developed a heart condition in the summer of 2004 which eventually required surgery. Hence the project was shelved – albeit temporarily.

My interest and enthusiasm was subsequently rekindled as a result of reading several football books which had each been written to commemorate major milestones in the professional game. No-one could convince me that the exploits and accomplishments of my own dad and his former Fryston team-mates were any less relevant, valid or interesting – certainly to their families, friends and, indeed, the town of Castleford – than their supposedly more illustrious contemporaries of the professional game.

One of these books was Simon Hattenstone’s The Best of Times: What Became of the Heroes of ’66? in which he spoke to members of England’s 1966 World Cup-winning team, forty years on from their triumph over West Germany. A second book, The Lost Babes: Manchester United and the Forgotten Victims of Munich, by Jeff Connor, comprises a fiftieth-anniversary reflection on the nature and consequences of the 1958 Munich air disaster in which the majority of Matt Busby’s great side tragically lost their lives. Whilst each of these commemorative texts was undoubtedly inspirational, it was a third book, Johnny the Forgotten Babe: Memories of Manchester and Manchester United in the 1950s, written by Neil Berry, son of Johnny Berry, the United right-winger and survivor of the Munich plane crash, which had the most powerfully resonant and animating effect. I was therefore now hell-bent on producing a commemorative publication to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the final.

I set about this task in two ways: firstly, by delving back into newspaper reports of earlier seasons in the club’s history; and second, by interviewing as many surviving members of the Fryston and Thackley teams as I was able to track down. I was initially intent on writing nothing more than a succinct ‘journalistic’ article on the final, based on relevant press accounts and the recollections of these former players. However, the more I began to excavate the newspaper reports, the more I became aware of the extent to which such knowledge was necessary to appreciating the full significance of Fryston’s appearance in the 1963 final, and of how it also provided a fascinating insight into a remarkable, virtually forgotten and hitherto undocumented local football culture. Thus, between August 2010 and the winter of 2012-13, Fryston Colliery’s pursuit of the ‘ultimate prize’ became transformed into an obsessive pursuit of my own.