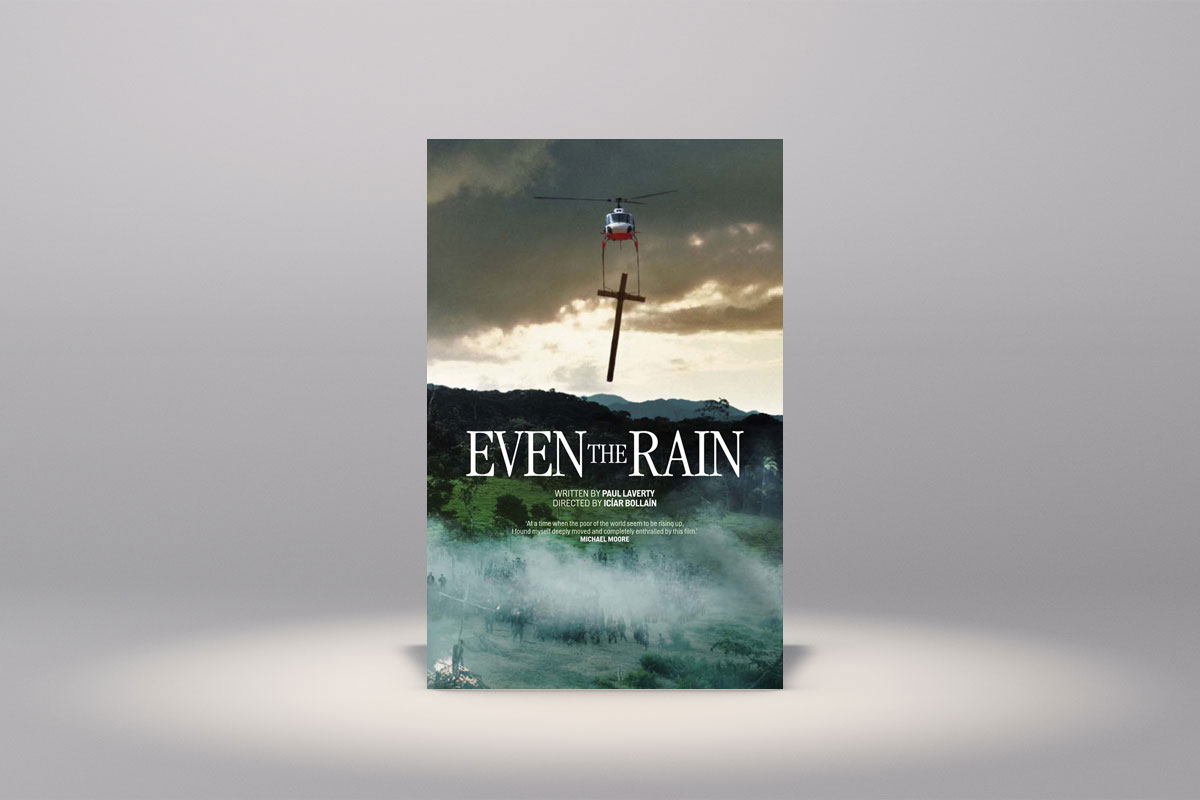

An extract from Paul Laverty's introduction to Even The Rain.

Around ten years ago the brilliant historian Howard Zinn got in contact with me after seeing a film called Bread and Roses, directed by Ken Loach and written by myself. He wondered whether I might be interested in writing a script inspired by the spirit of the first chapter of his iconic book A People’s History of the United States. I had a great passion for this book long before I met Howard and, in many ways, it was a dream come true to try and engage with a key moment in our history: the arrival of Columbus in the so-called New World. This is not the history of Columbus as the great discoverer, but instead it tells of what Columbus set in motion on his arrival among the Taino Indian population. The very first page of the book quotes from Columbus’s own log: ‘With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.’ This first chapter, and indeed the whole book, is a homage to the resistance of ordinary people fighting those who have tried to subjugate them in different ways throughout history.

Howard wrote in his introduction: ‘I don’t want to invent victories for people’s movements. But to think that history-writing must aim simply to recapitulate the failures that dominate the past is to make historians collaborators in an endless cycle of defeat. If history is to be creative, to anticipate a possible future without denying the past, it should, I believe, emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together, occasionally to win. I am supposing, or perhaps only hoping, that our future may be found in the past’s fugitive moments of compassion rather than in its solid centuries of warfare. That, being as blunt as I can, is my approach to the history of the United States. The reader may as well know that before going on.’

Getting this film made has been a ten-year obsession, but the spirit of the above is what kept the effort alive during some very treacherous moments.

Howard helped enormously by sending me many of his own books for my research. It was a colossal effort to engage with the grand narrative and investigate what life was like five hundred years ago. To write a script, you don’t just need to know what happened but you have to smell it; you need to get under each character’s skin, and try to imagine what the world looked like from their point of view, whether it’s a Taino child who first saw a bald and exhausted sailor land from Spain, or a young Catholic priest facing a furious congregation of colonists as he preached in favour of Indian rights. Howard at last gave me one terrific piece of advice, ‘Stop reading. Start writing!’

I wrote the first versions as entirely period pieces, under the title Are These Men?, inspired by a question asked by a Dominican priest Padre Antonio Montesinos, who preached in March of 1511 in what was probably the first voice of conscience against the new Spanish empire. His denunciation of the mistreatment and murder of the indigenous population was passionate and brilliant: ‘Look into an Indian’s eyes. Are these not men? Do they not have rational souls? Are you not obliged to love them as yourselves?’ Such dangerous opinions probably cost Montesinos his life.

The next stage was one familiar to many writers: the day of the double emails. I opened them in order. The first was a delighted one from Howard saying the project had been approved, and if I remember correctly was budgeted at around eighteen million dollars with casting just about to begin. The sweet adrenalin rush lasted all of thirty seconds. The second email was a brief note from a subdued Howard. He didn’t understand the reasons, but the project had been cancelled.