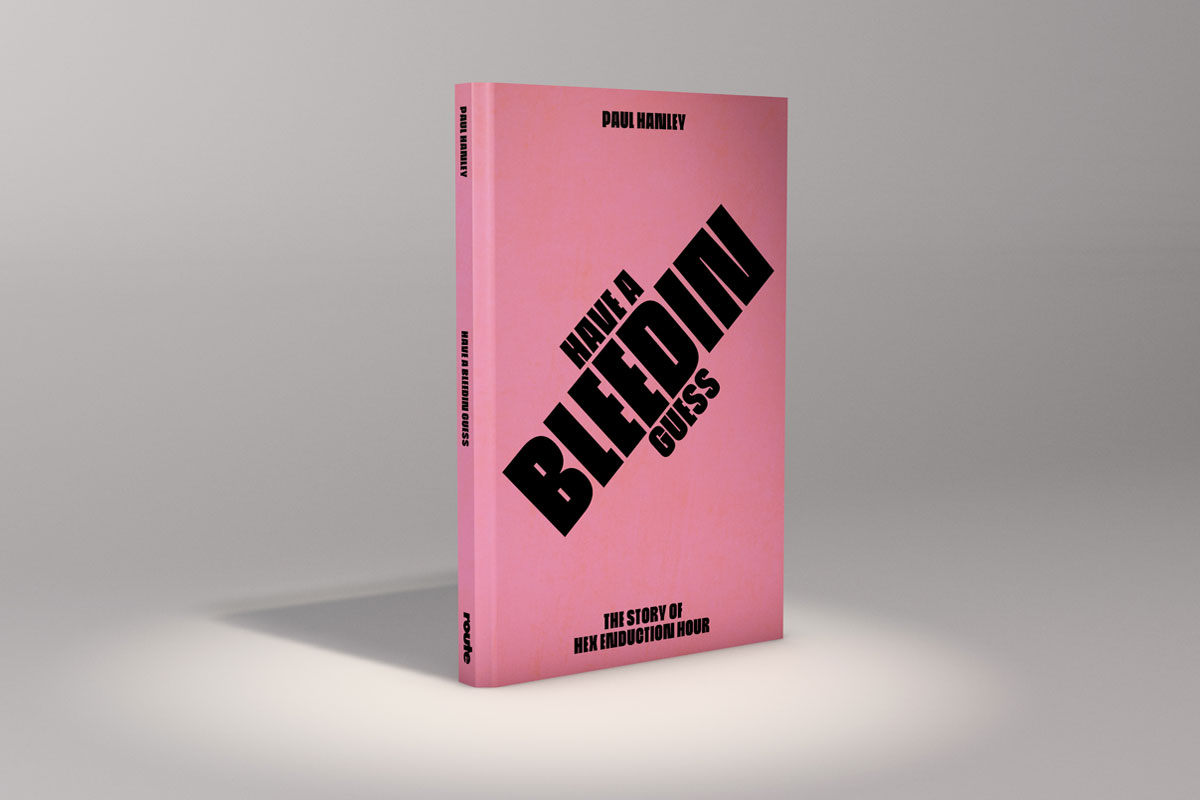

Paul Hanley's introduction to Have A Bleedin Guess: The Story of Hex Enduction Hour.

I’m still very proud of that album. It’s the one everybody talks about, and I can see why.

Mark E. Smith, 2009

There’s always some cunt who wants to ask me about a masterpiece I made in 1982.

Mark E. Smith, 2015

Why would you want to talk about an album you made 37 years ago? Well, even Mark E. Smith could see why Hex Enduction Hour, The Fall’s fourth LP, remained one of their most critically lauded and fondly-remembered. If you’ve read either Renegade or The Big Midweek, you’ll also know that the story of The Fall is an interesting one in itself. If you’re a fan of the group who’d like to know more about the way the group worked, then the period when Hex Enduction Hour was created is a good place to start.

John Doran: Even if it’s a fool’s errand trying to decide which is the greatest LP out of The Fall’s huge back catalogue of albums, many fanatics of the group will tell you that the worst thing you can say about Hex is that it’s their equal best at the very least.

Given that it was issued in the heyday of vinyl, most labels presented with sixty minutes of music would have chosen to release it as a double album. After all, Exile on Main St. is only seven minutes longer, and London Calling would be pretty much the same length as Hex but for the last-minute, unlisted addition of ‘Train in Vain’. In fact, Hex would have been longer than both if ‘And This Day’ hadn’t been pruned down to a more manageable length (10:23!) so the album would fit its title. In some ways it’s a shame Hex Enduction Hour isn’t a double – it’s certainly capable of shouldering the extra gravitas such a designation customarily infers. Of course, it’s likely a desire to avoid such jaded pre-conceptions is precisely what made Mark E. Smith insist that the songs were crammed onto two sides of a single album.

Because of the way The Fall worked in those days, Hex and its contents can’t be discussed in a vacuum. Even though Fall records were released with alarming regularity in the early eighties, recorded output was still unable to keep pace with the band’s prolific songwriting. Though 1982 saw the group release some twenty new tracks, many of them, including most of Hex Enduction Hour, had vanished from the set by the time we toured Australia and New Zealand in July and August that year.

If we count from when Karl Burns returned to the group, which we probably should, then the line-up that recorded Hex lasted from May 1981’s European tour, when Karl and I played on alternate nights, until December 1982, when Marc Riley was dismissed. In that 19-month period, the group played around 130 gigs: there were four trips round the UK, tours of the Netherlands, West Germany, Belgium, the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Iceland, and even a brief excursion to Greece. The Fall released three singles, two of which weren’t on an LP, and two albums. There was also the customary session for John Peel and two contemporaneously released live albums which are still in circulation today. Clearly, for the seven people that comprised the group at that time (the six band members and Kay Carroll, our manager) The Fall was pretty much all we did. Hex Enduction Hour was just a part of it.

None of which is to imply it isn’t a coherent and discrete piece of work. Though two of its tracks were recorded in Iceland before Karl was officially installed as a second drummer, most of it was recorded over a two-week period in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, and has a palpably homogenous feel. Mark was determined to present his new label Kamera with a product that would sell well and thereby put two fingers up to his old label, Rough Trade. If the circumstance of its recording afforded it a more singular vision than its predecessor, Grotesque, then it definitely fostered a degree of finesse that its follow-up, Room To Live, couldn’t hope to emulate.

While what went on during the Iceland and Hitchin sessions will inform much of what follows, documenting the making of Hex Enduction Hour isn’t like discussing Rumours, or even Blood on the Tracks: its recording was part of a process. What’s more, the Fall process often subverted the rehearse-record-tour cycle by skipping the rehearsal bit – it wasn’t unheard of for a song roughed out in a soundcheck to be part of that night’s set. The oldest song on Hex Enduction Hour was first played live as early as August 1980. The group released an LP, a six-track ‘mini-album’ and two singles before it made its way onto vinyl, but it fits Hex Enduction Hour’s atmosphere perfectly. Someone in The Fall knew what they were doing. Hopefully by the end of this you’ll have some idea too.

While it would be remiss of anyone endeavouring to tell the story of an album to not attempt at least some discussion of its lyrical content, deciphering a song’s words inevitably involves more theorising and/or guesswork than the other aspects of the story. Moreover, in some instances, discussions about ‘authorial intent’ become all but meaningless anyway – Mark has declared on occasion that he wasn’t aware what his intentions were when writing a particular lyric.

Mark E. Smith: I always try and put a little crack in it, and I always try and put lyrics that mean nothing and like jumble it all up […] Lyrics change shape and meaning all the time […] and do you know, I don’t always have a fucking clue what I’m saying. They can be just off my head. I don’t mean I’m off my head. I mean the words just come off the top of my head. It’s a bastard because when we have to do it live it means I have to sit down and listen to them and play it again and again. But some of my best songs are like that. A quarter of it is done on the spot. If you write everything down it’s chaos.

So, ‘Have a bleedin guess’, along with ‘What’s it mean? What’s it mean?’ from ‘New Puritan’, should be viewed as Mark E. Smith’s default retort to those who would attempt to decode and thus demystify his lyrics. As with many artists (as in ‘people who make art’ rather than ‘recording artists’), attempts to limit the meaning of Mark’s works to what he was thinking when he created them risk diminishing those works immeasurably. Or as he himself put it:

Mark E. Smith: When I started buying records, the ones I liked were the ones I could only half-understand. What I don’t like about a lot of records today is that they’re too clear. There’s no fascination or mystery left. […] This culture where you have to explain everything all the time, what you’re doing, puts a clamp on you. It’s a bit of a trap.

So, does ‘The Classical’ mean what he meant when he first wrote it? Or what he believed when he sang it onstage four months later? The flip side of such diversions into ‘new criticism’ is the worry that Mark’s lyrics, and thus Mark himself, are afforded higher status by dint of one reading more into them than is actually there – ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ by way of Being There. And Mark was often his own worst enemy in allowing that belief to propagate, as renowned Manchester music journalist Paul Morley has admitted:

Paul Morley: What if he wasn’t a genius, he was just an old drunken tramp that when he got really drunk started to spout phrases that made a kind of sense and we read too much into it?

It’s a good quote, and it’s something that has crossed many people’s minds at one time or another, but it’s obviously not true, as Morley knew when he said it. When he could be bothered, Mark had both the erudition and self-taught literary expertise to disprove this theory in an instant. There were periods of his life when he probably didn’t do that often enough, but his disinclination to justify himself is one of the main differences between The Fall and every other group. He really didn’t care whether you got it, it was your loss.

In short, any interesting theories about the words, whether my own or advanced elsewhere and quoted here, are just that. And the one thing we can be sure of is that Mark would dismiss them at a stroke.

Another difference between The Fall and other acts of similar vintage or older was that Mark E. Smith steadfastly refused to make The Fall’s history part of the act. He was so stubbornly uninterested in looking back that it alienated a section of his potential audience, which in turn had a direct impact on his earnings. Whether that made them a better live prospect depends, I suppose, on your attitude to nostalgia. Personally, I’ve always been delighted when Buzzcocks played ‘Boredom’ (or ‘Nostalgia’ for that matter), when Lydon sings ‘Public Image’ or when Johnny Marr strums the opening chords to ‘How Soon Is Now?’. It’s not, of course, what I expected of The Fall. Because for Mark E. Smith, The Fall was always about now.

Stewart Lee: Compared to The Fall, even Dylan’s apparently sacrilegious approach to the casual rephrasing of his own legacy of song seems accommodating and respectful. … Smith refuses to become a keeper of sacred relics.

Re-evaluating his group’s prodigious back catalogue was never a priority for Mark E. Smith. That doesn’t mean that I, or anyone else, should have felt the same. Trying to follow Mark’s lead when deciding which Fall product should be held in the highest regard was always as pointless as it was impossible, not least because he was an inveterate revisionist, and often wilfully contradictory from one pronouncement to the next, as illustrated by the two quotes above. This reached its hilarious zenith in 2009 when he was often to be found disputing both facts and opinions as reported in his own autobiography. Besides, any work of art transcends its author’s intentions the moment it enters the public domain. There is also the obvious point (to some at least) that he wasn’t the author of Hex Enduction Hour, he was a co-author. There were six people involved in the writing, and seven in the performance, of the material that constitutes Hex, and no one was reading sheet music. I know this because I was there.

Perhaps the overriding, and certainly the saddest, reason why now is a good time to re-evaluate Hex Enduction Hour is that the difference between current Fall fans and those Mark liked to call ‘look back bores’ has been eradicated by his death. The idea that harking back to a bygone era is somehow disrespectful to the current incarnation of The Fall has finally gone forever: it’s all the old stuff now.