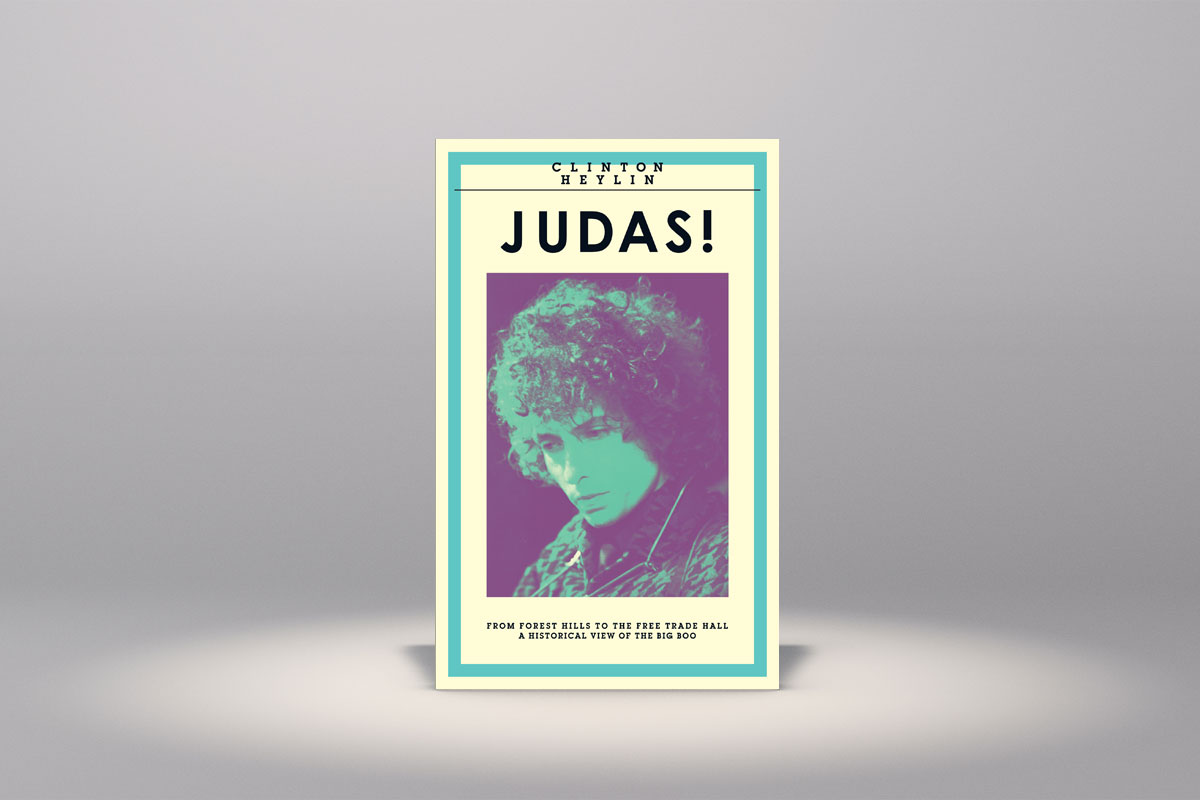

Already weary from a confrontational world tour, and beyond tired of the media circus, Bob Dylan held a press conference on 3rd May 1966 shortly after he arrived in London in advance of the British leg of his tour. It did nothing to calm the growing hostility towards the artist. This extract from Clinton Heylin’s book JUDAS! paints a picture of how it went.

Bob Dylan arrives in Britain for his second British tour on Monday (May 2)—and is bringing his American backing group with him. The group—just called The Group—will play all Dylan’s British dates with him. They will accompany the singer for half of each concert and he will do the other half alone.

—‘DYLAN BRINGS OWN GROUP’, MELODY MAKER, APRIL 30 1966

This brief news story, in the music paper most British Dylan fans liked to read, served as an all-important backdrop to his May 1966 UK tour, scheduled to run from the fifth to the twenty-seventh. To those of a folk-minded disposition, for whom two electric albums and five electric singles were not enough of a clue as to Dylan’s ‘current bag’, it confirmed their worst fears. It also suggested they should look to scalp any tickets already purchased—especially in London and Manchester, where shows were already sold out.

Whereas in 1965 articles announcing how ‘The Beatles Dig Dylan’ and whether an acoustic troubadour could be a poet had lit the way for Dylan’s arrival, by 1966 he was a bona fide pop star with a #1 album (Bringing It All Back Home), a #4 album (Highway 61 Revisited) and three Top 10 singles (‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ and ‘Positively 4th Street’) to his name, all in the twelve months since last he played the City Halls of Albion.

This time, he needed no advance hype to sell out a full tour of the British Isles. Nor did he need the press to follow him around firing questions. So, instead of multiple formal and informal press conferences, backstage interviews with student reporters, one-on-one interviews with all the important music weeklies and the odd impertinent questionnaire, he agreed to exactly one press conference at the Mayfair Hotel—having relocated from the Savoy (perhaps still unhappy about the previous year’s ‘who threw the fucking glass’ incident, captured in Dont Look Back). At the press conference scheduled for the day after he flew in, he would again use the film crew as personal foils in another grand charade.

Not surprisingly, members of the English music press were a little put out to find themselves sitting cheek to jowl with ‘the establishment press … [who] didn’t understand what was going on in the musical arena’. As to what they could expect, they might have seen one of the questionnaires he had filled in the previous May, for Jackie, which listed the ‘loves and hates of Bob Dylan’. In the former category he had included ‘originality in anybody—makes such a big difference when they’ve got their own ideas to give out’. Personal bugbears included, ‘Rules. Why should we have them? … the importance that money has in our society …[and] that strange feeling when you come into a room that something’s gone wrong.’

There was certainly a ‘strange feeling’ in the Mayfair Hotel suite on the May day Dylan deigned to lock horns with another querulous quorum. Even familiar faces were given short shrift, Dylan ‘blanking’ Max Jones before making him the butt of one of his best one-liners. When Jones suggested he had heard he didn’t write protest songs any more, Dylan fired back, ‘All my songs are protest songs. You name something, I’ll protest about it. All I do is protest.’

Jones had been the first person Dylan called on when he visited London in December 1962 (Jones having been recommended by Ramblin’ Jack Elliott), and had been someone Dylan opened up to on both previous May visits, in 1964 and 1965. So he was bemused to find Dylan being wholly uncooperative but relieved to find he was not singled out for the treatment, prompting the headline to his resultant feature, ‘Will The Real Bob Dylan Please Stand Up?’:

Chatting up Bob Dylan … used to be easier, but as he gets older he seems to grow more and more fed-up with questions. Very difficult it is getting him alone. When you’ve failed in that, the next hindrance is his reluctance to impart information. It’s not that he won’t answer. But his replies, sometimes oblique and often designed to send-up, carry vagueness to the borders of evasion. Asked if the label folk-rock, sometimes applied to his current music making, meant anything to him, he queried back at me: ‘Folk-rot?’

To raise the level of the conversation a bit, I injected the names of Bukka White, Son House and Big Joe Williams. Did Dylan listen to such blues singers?

‘I know Big Joe, of course. But I never listen to these men on records too much. Lately I’ve been listening to Bartok and Vivaldi and that sort of thing. So I wouldn’t know what’s happening.’

Before we parted, another journalist was questioned by Dylan. He mentioned his paper. Dylan looked blank. ‘It’s the leading musical paper in the country,’ said the reporter firmly.

‘The only paper I know is the Melody Maker,’ was Dylan’s reply. One way or another he makes it clear he’s not out to win friends and influence newspaper men.

The reporter from the ‘leading musical paper in the country’ was Keith Altham, NME’s hippest reporter. But even this well-known face made very little headway with the man behind the shades when trying to raise the tone:

For posterity’s sake, I framed a question which might have been construed as ‘being aware’ … why is it that the titles of his recent singles, like ‘Rainy Day Women #12 + 35’ apparently bore no connections with the lyric? ‘It has every significance,’ returned Dylan. ‘Have you ever been down in North Mexico?’ ‘Not recently …’

A nonplussed Altham turned his attention to ‘a large gentleman with a grey top hat and movie camera permanently affixed to his shoulder, lurch[ing] about the room like Quasimodo, alternately scratching his ear and his nose, with the occasional break to “whirr” the machine in the face of perplexed reporters’. It was Pennebaker, of course.

Altham also observed ‘a lady in grey denims wav[ing] what appeared to be huge grey frankfurters about … [which] proved to be microphones attached to tape recorders’. The lady was Jones Alk.

Mrs Alk—whose husband Howard was hovering somewhere in the background—found herself an unwitting bit-part actor in another of Dylan’s games for May on the one occasion the ‘establishment press’ managed to ruffle Dylan’s feathers. He found himself ducking a series of questions regarding his recently reported marriage, a touchy subject at the best of times, until the mirror behind the glasses almost cracked:

Q: Are you married?

A: I’d be a liar if I answered that, and I don’t lie.

Q: Well, tell the truth then.

A: I might be married. I might not. It’s hard to explain really.

Q: Is she your wife? [points to Jones Alk].

A: Her? Oh yeah, you can say she’s my wife.

Jones Alk: No, my husband wouldn’t like it.

Q: Are you married to Joan Baez?

A: Joan Baez was an accident … I brought my wife over last time and nobody took any notice of her.

Q: So you are married then?

A: It would be very misleading if I said yes, I was married; and I would be a fool if I said no.

Q: But you just said you had a wife.

A: That depends on what you mean by married.

The four music press reps in attendance—Jones and Altham, plus Record Mirror’s Richard Green and an unnamed correspondent from Disc & Music Echo—valiantly tried to stem the tide of inanity, but it was a losing battle. Time to just sit back and enjoy the ride:

Q: What do you own?

A: Oh, thirty Cadillacs, three yachts, an airport at San Diego, a railroad station in Miami. I was planning to bus all the Mormons.

Q: What are your medical problems?

A: Well, there’s glass in the back of my head. I’m a very sick person. I can’t see too well on Tuesdays. These dark glasses are prescribed. I’m not trying to be a beatnik. I have very mercury-esque eyes. And another thing—my toenails don’t fit.

Q: Tell us about the book you’ve just completed!

A: It’s about spiders, called Tarantula. It’s an insect book. Took about a week to write, off and on … my next book is a collection of epitaphs.

Q: Who’s the guy with the top hat?

A: I don’t know. I thought he was with you. I sometimes wear a top hat in the bathroom.

Eventually, as in Copenhagen, ‘Mr Dylan started to interview the journalists’, as things again turned sour. After he told the Daily Sketch’s Dermot Purgavie they were boring, ‘the stroppier ones among us indicated that they weren’t too enchanted by him, either’. At the end of proceedings, the Sun’s Christopher Reed spoke for his fellow Fleet Streeters when he observed how Dylan had ‘managed to answer questions for an hour without really answering any of them at all’.

As the press filed out, a CBS publicist suggested, ‘Cliff Richard was never like this.’ Mr Reed now had his headline. Purgavie was equally sniffy about the uncooperative artist in his Sketch headline, ‘At least in his songs Mr Dylan has something to say.’ On the other hand, England’s thriving mid-sixties music press, to a man, sided with the star. Appropriately, Disc & Music Echo, the weekly that had run his notorious ‘Mr Send-Up’ interview the previous May, seemed particularly amused:

Bob Dylan arrived preceded by an almost violent reputation for being rude and uncooperative. He is rude—to people whom he considers ask stupid questions. He is uncooperative—he doesn’t like giving up his precious free time for individual interviews. But Bob Dylan is also a very sympathetic man with a vast sense of humour. He explained why he was wearing dark glasses. ‘I have glasses at the back of my head too. Look. I’m not trying to come on like a beatnik. I have to wear them under prescription because my eyes are so bad.’ … He played with a huge ashtray and then, this man who has said more with his songs than many say in ten thousand words, was asked some of the most ridiculous questions in the world. Things like a barrage of question[s] about whether he was married as though it was the most important thing since the nuclear bomb. No wonder he lost his patience.

Record Mirror’s Richard Green took equal delight in quoting ill-advised questions from the straight press, juxtaposed with the non-sequiturs Dylan provided for answers. Like Altham, he had realised immediately that ‘the farce … was obviously being staged’ for the cameras’ benefit and played dumb:

Until then, I’d always thought that Juke Box Jury was the funniest thing ever. But Dylan’s handling of the press left that standing. Asked if he had any children, he said, ‘Every man with medical problems has children.’ Asked what his medical problems were, he said, ‘Well, there’s glass in the back of my head and my toenails don’t fit properly.’ Dylan’s bunch of assorted film cameramen and sound recordists were happily enjoying the farce which was obviously being staged for their benefit. They continually trained cameras on the reporters and pushed weird microphones at people who spoke. Then somebody mentioned folk singer Dana Gillespie and at once Dylan brightened up. He laughed out loud, smiled broadly and asked, ‘Yeah, where is Dana. Come on out, Dana. I’ve got some baskets for her. Put your clothes on.’

As the penultimate press conference of the world tour wound to its predictable conclusion, Keith Altham went looking for one last usable quote, not from Dylan but from one of his sidekicks: taking ‘one of Dylan’s undercover agents to one side (I knew he was a Dylan man as he had dark glasses on) I enquired why a man with Dylan’s obvious intelligence bothered to arrange this farce of a meeting’. It was Bobby Neuwirth, whom he recognised from the previous year. He wasn’t about to sugar-coat it; ‘Dylan just wanted us to come along and record a press reception so we could hear how ridiculous and infantile all reporters are.’

For the remainder of his time in the British Isles, Dylan kept the press at arm’s length—clearly a conscious decision. The one time he decided to rebut accusations fired his way by reviewers of the shows, it would be from the Royal Albert Hall stage to a captive audience.

Bob Dylan 1966 London Press Conference

01 January, 2023