When Ada Wilson wrote Red Army Faction Blues, there were many things he knew about his protagonist Peter Urbach and many things he had to speculate on. It turns out he wasn’t that far off. Since Peter Urbach’s death in May 2011 – just after Ada had finished writing the book – more details about the life of this Polish undercover policeman have been revealed. Here, Ada shares some of the things he’s learnt.

In Red Army Faction Blues, I put him in Miami, which wasn’t too far off the mark in the end. Some thought South America, but it seemed logical that the US would be looking after him.

It turns out he’d been in California all these years, though it’s not certain for how many of them under his own name. The obituary that appeared on the web though, extracted from the Santa Maria Times, boldly named him Peter Urbach once more.

He’d worked for many years in the plumbing and pipefitting business over in the States, and helped build, among other things, the Diablo nuclear power plant.

His first wife didn’t last long in the USA, returning to Germany without her children back in the 70s. By the time of his death, he’d twice remarried and his third wife knew nothing about his time in Berlin. In the novel, I gave him a son and a daughter, but in reality he had two sons – Thomas and Martin – by the time he left Germany.

Günter Langer could have corrected that detail and is well qualified to talk about the key events in Germany which form the setting for Red Army Faction Blues. He was close by on 2nd June 1967, when fellow-student Benno Ohnesorg was assassinated in Berlin.

Later he founded the International News and Research Institute with Rudi Dutschke, and after Dutschke’s shooting, lived for a time in the Wieland Community and drifted with the Wandering Hash Rebels, a number of whom would go on to become the Movement 2 June.

He was the editor of the German underground magazine Agit883 which served as the mouthpiece for all of the underground groups. Today, he also lives in the USA, but for many years taught in Berlin.

He not only knew Peter Urbach, in those turbulent times in the late 1960s, but counted him both as a friend and ‘comrade’.

Until in 1971 Urbach was revealed as an agent provocateur, a trained undercover police officer, who saw himself as boldly entering ‘the lion’s den’ in the frontline defence against Communism.

Not long after this, Gudrun Ensslin – the leader of the Red Army Faction who was eventually to die in Stammheim prison in 1977 along with Ulrike Meinhoff and Andreas Baader – would give Günter a photo of Urbach and ask him to print it in Agit883, under the slogan ‘Traitor!’, while implying he was ripe for assassination.

Langer demurred, although Agit883 was hardly reticent in printing inflammatory material – some of which would certainly see him behind bars were it to be published today.

‘In spite of his treachery, I wasn’t relieved to hear of Peter Urbach’s death,’ he says. ‘On the contrary, I always hoped to one day be able to take him to task for what he did. Even forty years later, all of the surviving RAF members who have deaths on their consciences are now free and can talk about their actions.’

According to his son, Urbach ’smoked like a factory’ and drank heavily, ending up on a kidney dialysis machine and succumbing finally to renal failure.

Günter Langer, however, has put together a very detailed account of all the known facts about Peter Urbach and his activities in Berlin on the SDS website:

It’s in German, so for English speakers I’ll outline the key points here.

Peter Urbach is reported to have lost his parents in Poznan – a Polish city doomed too often by the tug and pull of expansionist national policies by surrounding empires – at the end of World War 2. He spent his childhood in a war orphanage in Berlin with his older brother Hartmut. There are many references to him later using these formative experiences to win friends and inspire trust.

He was a good police officer, it’s reported, and back then, a talented athlete – there was even talk of him making West Germany’s Olympic team.

But he set his sights on bigger kicks. He was, says Langer, an ‘adrenaline junkie’.

The first time the two met was at Kommune 1’s factory on Stephan Street in Berlin where Urbach’s practical skills – especially in pipelaying – proved pretty useful to the friends he’d recently made.

Later at the SDS headquarters at 140 Ku’Damm, he would show Langer a gun and ask if he wanted one.

‘I was pretty confused and declined. He even invited me to his home at that time, where I met his wife and kids.’

According to Reinhard Mohr, journalist for the newspaper Der Spiegel, ‘Peter Urbach worked for practically everyone. For the West German secret service, the Stasi and for Kommune 1.’

It’s a compelling idea, and certainly made him an attractive candidate as the protagonist of my novel.

Günter Langer, however, thinks this unlikely, laying the orders for his actions squarely with Berlin’s mayor of the time, Kurt Neubauer, and his State Office for Constitutional Protection (LfV). At the same time, he also mentions the continued presence in Berlin of many remaining members of the dissolved US agency, the CIC.

In the immediate post-war period, the CIC operated in the occupied countries, particularly Japan, Austria and Germany, countering the black market, and searching for and arresting notable members of the previous regime.

The CIC was also involved in the Alsos, Paperclip and TICOM operations, searching for German personnel and research in atomic weapons, rockets and cryptography. Recruits after World War 2 included Klaus Barbie, the 'Butcher of Lyon’, a former Gestapo member and war criminal.

At the time he met the students of Kommune 1, Urbach told them he’d been sacked for stealing from his job on the Berlin S-Bahn – a service perversely controlled by East Germany through all of its West Berlin route stops during the city’s years of division. Langer believes Urbach may have been deliberately planted in that job in order to perform small acts of sabotage and so embarrass the East German regime.

It earned him his nickname ‘S-Bahn Peter’ and he went on to have a hand in a number of the key events in the history of the German counter culture of the late 1960s.

One was certainly the distribution of Molotov cocktails outside the offices of press baron Springer on the night Rudi Dutschke was shot, leading to the first real night of violent protest.

A second was the parking of a truck full of stones along the route of a demonstration in November 1968 which resulted in the ‘Battle of Tegeler Weg’, in which for the first time, the demonstrators gained the upper hand, with 130 police officers injured.

By February 1969, Urbach was asking many of the leading student groups to hide bombs for him – the existence of which gave the authorities grounds to conduct extensive house searches and led to a number of arrests.

‘The fact remains that the authorities were responsible for the original distribution of these devices,’ says Langer, while pointing out that they couldn’t really be classed as ‘explosives’ as such at all, with little more potential impact than Molotov cocktails.

One of these devices, however, would end up being planted in the Jewish Community Centre in Berlin on the anniversary of Crystal Night. A very significant date, 9th November 1969.

By that time, though, Langer says Urbach had lost all contact with the perpetrators.

In the end, he adds, Urbach’s actions were a contributing factor to the criminalisation of the Left in Berlin at that time, and also to the radicalisation of some of the urban guerrillas and their descent into madness.

The point of regular fiction is to bring characters to life, and – if they capture the general imagination – render them immortal. It’s strange to have done virtually the opposite with Red Army Faction Blues – fictionalise a real person only to obscure the real facts, which it appears anyway, will now never be known.

Urbach apparently died on 3rd May 2011, although the obituary didn’t surface until after the novel was finally published.

Somehow for me, it feels like a personal slight. At the back of my mind – once I’d fixated on him – I had this idea that the book would, one way or another, get to him, and that he’d emerge from his long exile to set the story straight.

Now, of course, that won’t happen. This is how history is unwritten, then.

‘Kurt Neubauer is now ninety years old and demented,’ Langer concludes. ‘His former intelligence chief has disappeared and the files kept on Urbach have most likely been disposed of. The trail has gone cold.’

Ada Wilson, June 2012

Adrenalin Junkie | The Trail Has Gone Cold

01 January, 2023

Related Products

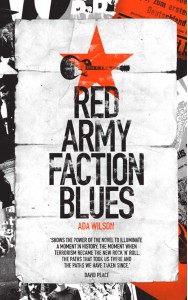

Red Army Faction Blues

A coalition government. A widely mistrusted ruling elite. Riots in the streets and heavy-handed police tactics. Welcome to West Berlin, 1967. Undercover agent Peter Urbach is tasked with infiltrating a group of radical students whose anti-consumerist message is not without propaganda value on both sides of the Wall. Soon, high-minded political activism wi..

Read More