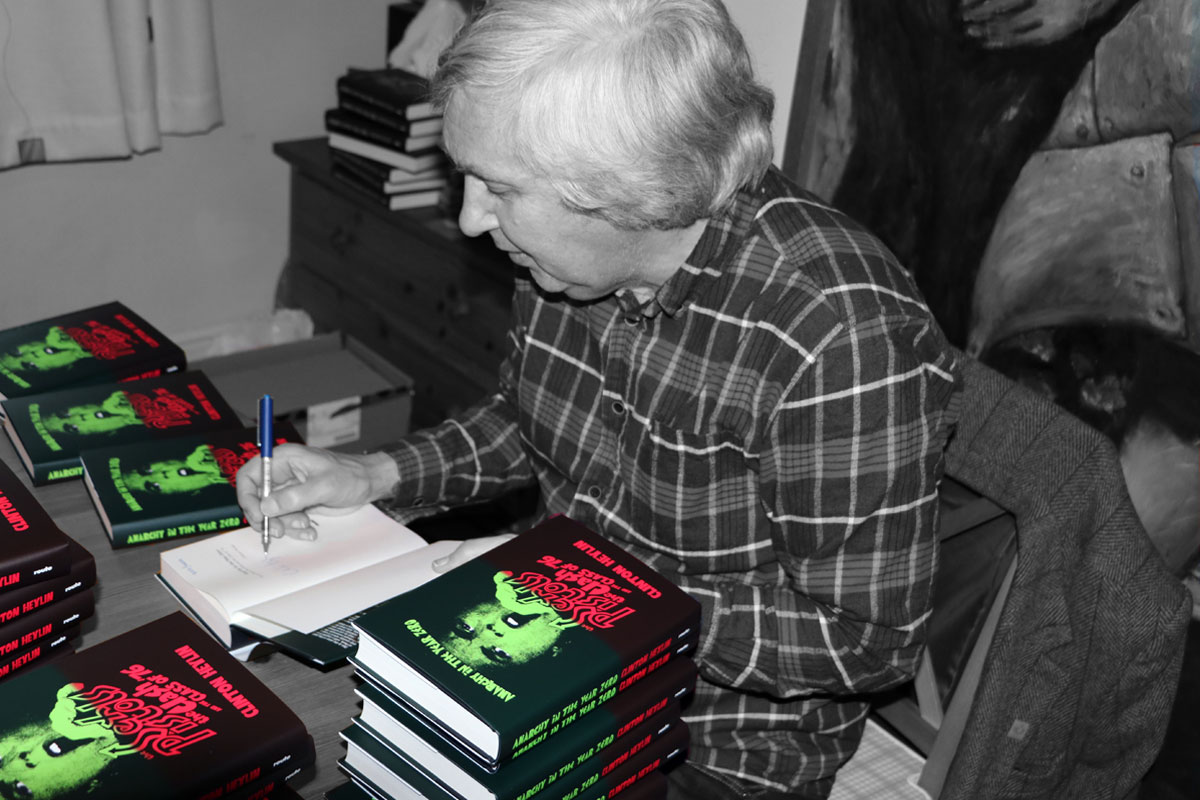

When Clinton Heylin called in to Route HQ to sign copies of Anarchy in the Year Zero, he took time out to answer some questions about the book.

Why did you write the book?

There have been punk histories over the years, and obviously I wrote a relatively famous one myself, From the Velvets to the Voidoids, all of 24 years ago, but I always thought this was unfinished business. I think one of the extraordinary things about the Pistols story which nobody really picks up on is this thing about direct inspiration. People went and saw the Sex Pistols then formed a band. I don’t mean that they saw them on the Ed Sullivan Show or that they heard a record, quite liked it, and several years later became The Smiths, I mean they went, they saw, they became musicians. There really is no parallel in popular music, either before or after.

How does this book differ from other punk accounts?

Well obviously it’s very concentrated. It starts with the Sex Pistols’ first gig in November 1975 and it ends with the final gig of the Anarchy Tour in December 1976, so it’s very compressed. The point of doing it this way is to try and give a sense of the sheer momentum of that story. This is a band who have never made a record, they are making the front pages of all the music papers and appearing on television before they even have a record deal. It’s pretty revolutionary stuff. It’s an extraordinary story and in order to get that story and momentum across, you have to compact it into this very tight narrative of those initial 86 Pistols gigs with all the little spin-off bands, and everyone else in the shadow until the end.

You talk about spin-off bands, how would you describe the hierarchy of punk?

If you talk about the hierarchy of singer-songwriters, there’s Dylan and then there’s everyone else. The hierarchy of punk is the Sex Pistols and then everyone else. Obviously I am talking about English punk here, and with English punk you are either the Sex Pistols, or you’re directly influenced by the Sex Pistols, or you’re not punk. To be a punk band you have to have seen and been directly inspired by the Sex Pistols. It is not about whether you play fast or whether you play with barre chords or don’t know what a middle eight is. There are people who keep insisting that The Stranglers are a punk band, indeed that The Vibrators are a punk band, both of those bands were in existence long before the Sex Pistols and in neither case can it be said that they were directly inspired by seeing the Sex Pistols play.

What’s the distinction between Year Zero punk of 1976, and the punk of 1977 which most people associate with punk rock?

1977 is the year of punk in the same way that 1967 is the year of psychedelia. Sgt. Pepper came out in 1967, ‘God Save the Queen’ came out in 1977. In neither case was it the year of that particular movement. Psychedelia was pretty much dead and buried by the time Sgt. Pepper came out; the year of psychedelia was 1966. All the interesting things that were going on – Pink Floyd, The Move, Tomorrow, Happenings – were all happening in 1966, not 1967. Well, punk is a bit like that really; once it becomes a cultural movement, once the tabloids think they know what punk is, it’s over, because it has to be. Once any art movement becomes a public movement, it cannot retain its true self. At the end of the book I quote Lenin who said, ‘Whoever expects a pure revolution will never live to see it,’ which is actually what he said about the Easter Rising and he’s right on many levels. The thing that I try to tell in the book is that the original punk movement was incredibly elitist. All this ‘we are all in this together, it’s the working-class lads’ is all arrant nonsense. It’s being instigated by a guy who runs a fetish sex store on the King’s Road, this is not somebody who is trying to start an annex to the Socialist Workers Party. The elitism is there in the snobbery of the individuals – you can see it in the way they looked down on the people who turned up to see the Sex Pistols in November 76, let alone November 77. In the book I quote Steve Severin turning to Siouxsie Sioux at a gig at Notre Dame saying ‘It’s all over’ because all these people had turned up in bin liners.

Why did it all go so wrong for the Sex Pistols?

Punk is combustible, that’s really the point about it. The Sex Pistols are a train wreck because of the figures in the band and the man who oversaw the whole exercise, Malcolm McLaren; those five individuals were never going to be able to keep the thing together for any kind of period of time. They all had massive issues, unresolved. Johnny Rotten was a time bomb and that’s part of what made him so incredible. People who I interview in the book, people who talk about that period, they all say that over that year when he was in the original band, the transformation in Rotten was something to behold. But there are losses and there are gains; by the end of it he was a magnetic performer but he was also starting to believe his own publicity. Sadly, it was him that conspired to end the band more than McLaren, more than circumstances. Obviously the Bill Grundy show had an effect, but it’s really that he started to believe it was his band, and it never was.

Do you see McLaren as the charlatan he is often painted?

McLaren, I think, has been slightly dumbed-down in history, but it’s entirely his own fault. I have no sympathy for him on that front because obviously he set out to convince everybody that it was all some great master plan, which of course it wasn’t. He was making it up as he was going along, but everybody who worked with McLaren in that time period has great fondness for him, so you can put that aside. What perhaps he didn’t realise was just how successful the joke would become. What is amazing is to be able to go back and realise that he connects all the dots; he’s getting people to come down to see the Pistols from NME, from Melody Maker, he’s making phone calls, he’s pissing people off, he’s getting them to write things they don’t need to, he’s doing everything he can to make this happen and it’s inspired. He gets Chris Spedding to produce the Sex Pistols six months after the band started playing, that’s impressive. He then gets Chris Spedding to pick up the bill for it as well, which is even more impressive. He’s the only one of those punk entrepreneurs who didn’t get screwed over by the record labels, in fact he took EMI to the cleaners. He was shrewd, he understood how the business worked. Unfortunately, at the end of it, it sort of became a battle between him and Rotten and instead of these spontaneous happenings, he started to try to make things happen. I think that’s the turning point. Obviously there’s the incident with Nick Kent being beaten up at the 100 Club, we don’t really know whether McLaren was behind that, but whoever was behind it, it is a turning point because he was starting to try and make things happen when there was no need to.

What’s your connection to the story, were you there?

I was sixteen years old in 1976. I’d been going to gigs for 5 years and like everybody my age who read the NME religiously, I was waiting for the next big thing. NME and Sounds were the two weeklies that I read so I read Jonh Ingham’s two-page piece on the Pistols in April 76 and I remember thinking, ‘Oh yeah, okay.’ I didn’t hear about the first Pistols gig in Manchester until it took place. I knew someone at my school who’d been to that show and he’d told me about it. I was aware enough to know when they played the second time but I hold my hands up, the reason I knew about the second gig was really because of Slaughter and the Dogs. Everybody from South Manchester knew Slaughter and The Dogs, everybody was into Bowie and that kind of thing. My curiosity was not the Sex Pistols, it was seeing one of the local bands make good.

What happened when you saw the Sex Pistols then?

I have to say in my case all I really remember is the trouble because there was a lot at that gig and it got pretty hairy. I remember I split early, I didn’t see the end of the show. I was down the front and it was no fun, as they say. But, from that point forward, I kind of figured it out. I quote Linda Sterling in the book saying Slaughter and The Dogs were one thing and the Sex Pistols and Buzzcocks were another. Because Buzzcocks were in Manchester, I was more aware of them than the Pistols, and Spiral Scratch coming out was exciting, all of that. The Grundy show was only shown in London, but one of the things that people don’t talk about was seeing ‘Anarchy’ on So It Goes. It was absolutely extraordinary. Just to see a band like the Sex Pistols on TV had a profound effect. By 1977 I was seventeen, I was old enough to have a motorcycle and was able to start going to gigs on a regular basis. I saw pretty much everybody. It certainly was what I thought I was looking for all along. I’d grown up with Slade and T-Rex and all that so in that sense I always knew there was something up. I mean, I like prog bands, I still do, but I knew that they weren’t it.

In the book you talk about a small handful of people who were there and saw the Sex Pistols and they were all inspired to go on and do something else and get involved, would you count yourself amongst those?

Yeah, absolutely. I grew up reading the NME and had always wanted to write about music. I remembering replying to the ‘Young Colts’ advert that NME ran which Tony Parsons and Julie Burchill ended up getting jobs out of. I must have been one of the first people to buy Paul Morley’s Out There, the little fanzine that had a review of the Sex Pistols. I can’t remember reading that review, but I can remember where I bought the fanzine. I remember fanzines being a big inspiration, just the idea of them. I had access to a Zerox machine, which many people didn’t, because my dad had one in his office that I could raid to print my own fanzine. After the Sex Pistols I started a Public Image fanzine very early in 1978 when their first record came out. It was called Piles, Public Image Limited Information Services. I think we did 5 issues. I’d been listening to avant-gardy, proggy, kraut-rock stuff prior to punk so I didn’t have a problem with the direction things went in. My real love after the Pistols were bands like Wire and Siouxsie and The Banshees who were much more interesting to me than the na na na na na na. XTC were a great band, very underrated, and you could see all those bands for 10 bob. So it absolutely inspired me. The first book I wrote was From The Velvets to The Voidoids, which actually came out after my Dylan biography, but my first proper book was a punk book, and it continues to hold up for me and the music still holds up for me and the energy still holds up. I put on that tape of the Pistols at the Lesser Free Trade Hall and it never fails to galvanize me, I put it on and I’m like ‘yeah’.

A lot has been made of the impact that the DIY ethos has had on music in particular. Do you think the same applies to writing?

People forget how inspirational that punk writing was in the NME and Sounds and Melody Maker. Go back and read them. Jonh Ingham’s piece about the Sex Pistols is a great piece of writing. And to hear Johnny Rotten say ‘I want more bands like us’, remember this is an interview taking place just four months after the band was formed. To have the arrogance and the sheer chutzpah to say that, and then of course it all came true. It is an extraordinary piece of foresight, and that whole aspect, reading about punk – remember there were no records, the first record came out in November 1976, we’d been reading about punk for nine months at that point, and reading about it week after week after week, reading about these bands that we couldn’t go and see. I didn’t see The Clash or The Damned until 1977, so we were reading about these and wondering ‘What the hell do they sound like?’

Charles Shaar Murray’s memorable quote about The Clash being a garage band that should stay in the garage with the motor running, there’s something great about that line. I wasn’t a musician though I did form my own crappy punk band like everyone else did. We were called The Pits, and trust me, that’s what we were. I was the drummer, we were truly atrocious. We had some great songs, ‘Sleep a Little Longer Grandma’, ‘Baby I’m a Terminal Case’, ‘Thank You God Now Get Off’, the usual punk fayre. We headlined the Tewkesbury Punk Festival.

There is definitely that Punk DIY spirit in the writing too. It’s hard to think about that now in terms of social media, the internet and interconnectivity. Certainly for me, I don’t feel that the youth are as connected as the people in the book. The people in the book had to hunt to find what they were looking for, but that hunt is what inspired them.

The interesting thing about DIY writing is the ability to say what the hell you want. And now we’ve lost that. The constraints now, even though there is the pretence that you can have your own blog or whatever, the reality is that you cannot say what you think. Somebody will shut you down, somebody will distort what you say. In Chrissie Hynde’s autobiography, she made a comment about her own body and choices that she made and she was pilloried for it by people who’ve got no damned right, who’d done nothing. Think of the good that woman has done for women who want to also make artistic statements and all these people just laying into her. Whereas, one of the beauties of punk is not only the ability to offend, but the desire to offend, an actual determination to set out to think of the worst thing that you could say to somebody 40 years old and say it. Of course the establishment reacted with horror, but it was a battle worth fighting. If you believe in something, you should be able to shout it from the roof top.

What do you consider is the legacy of 1976?

Obviously, like all art forms, the legacy is in the art. And that doesn’t just mean the music, that means the image, the literature, that means everything that goes with it. I get slightly annoyed by people talking about punk happening in 2016, it’s like people talking about the new psychedelia, there’s no such thing, there can’t be because times have changed, you cannot have punk in 2016. In its pure state, punk ended the day that The Roxy opened. If you want to have a new music movement, think of your own name, don’t come up with somebody else’s. You can take inspiration from punk, but the inspiration shouldn’t be ‘I would like to be like that’. The last quote from Rotten in the book is ‘When I said I wanted bands to be like us, I didn’t mean exactly like us’. Punk was something that could only be very short lived.

Clinton Heylin Interview – Anarchy in the Year Zero

01 January, 2023

Related Products

Anarchy in the Year Zero

The story of the birth of Punk, with a capital P. How did it happen and why it still matters

Read More