A feature on how Ian Clayton recconected with his father after many years estranged.

The first time I met Ian Clayton it was to talk about his nine-year-old daughter, Billie, who was drowned in a canoeing accident in Wales eight years ago. Ian managed to save her twin, Edward, but couldn’t reach Billie in time. When Ian mentioned that he hadn’t seen his father for several decades, the estrangement paled in comparison with Billie’s loss. Even so, it seemed to add an extra layer of sadness to the story when Ian said his father had sent a message that he’d like to attend Billie’s funeral – the granddaughter he’d never met – but that Ian had “sent back word not to bother”.

I wrote that although Ian said he didn’t care about the rift, I suspected that somewhere inside he did. 'When I read that it brought me up short,' says Ian. 'It made me think maybe I should get in touch with my dad because he was getting on.'

One day, early last year, the phone rang at Ian’s home in South Yorkshire. 'Suddenly there he was, after all these years, telling me he was riddled with cancer and was phoning to say farewell, and would see me on the other side.'

As he’d been thinking of getting in touch with his father anyway it seemed churlish to resist. His dad, Sid, lived 60 miles away in Hull and Ian – a writer and TV documentary-maker – was due to give a talk at a working men’s club there a week later. 'I decided to go early and call in,' he says.

What happened next became the starting-point for his latest book, which charts not only the moving story of how he reconnected with his father in his final months but also relates the tale of how he spent a lifetime searching for men to take Sid’s place – only to find that the father figure he wanted was there all along.

Ian is from working-class Yorkshire stock: Sid worked in a variety of jobs, including a stint at a fairground. He always seemed to struggle with money, and when Ian visited him in Hull last year, the first thing he realised was that things hadn’t changed. 'The estate he lived on was one of those places where you look up and see a pair of underpants on a roof,' he says. 'I rang the doorbell and heard the sound of three bolts being opened and a dog yapping; and there was my dad, only he wasn’t the dad I remembered – he was a wizened old man with a stick.'

Ian followed his father into the cramped sitting room of his council flat, and then Sid said a curious thing. “He said: 'It’s been a long time, son, but me and your mum only wanted what was best for you. And I thought, bloody hell. If that was the best they could do I don’t know what the worst would have been like.'

Ian, 52, was the product of a fling that would have been as brief as a ride on one of his dad’s waltzers, if it hadn’t been for the ensuing pregnancy. 'My mum, Pauline, and my dad never loved one another,' he says. 'I never saw them holding hands, never saw any sign of affection between them. They married because they had to.'

Two more sons, Tony and Andrew, followed, before Pauline was struck down by what was always described as a 'nervous complaint' and kept threatening to put her head in the gas oven. Today, says Ian, he can see that all Pauline ever really wanted was a man who would love and cherish her. 'She wanted to put on a nice frock and be taken somewhere fun – as simple as that really. But my dad was a miserable old bugger. He didn’t know how to cherish her, he didn’t know how to look after her and he never took her anywhere.'

Looking back, Ian can see that part of what he fought against, all his life, was the idea that he was like Sid. 'He was gruff and uncaring. He was uneducated and sarcastic and cruel and rough. I didn’t want to be any of those things: I wanted to be gentle and kind, smart and educated – not ignorant like him.' If a relative ever told him he was like his father, Ian took it as an accusation; he’d wince and feel ashamed.

Growing up with Sid and Pauline was neither pleasant nor easy; there was never enough money and his dad was in and out of jobs. But then Sid got what seemed like a breakthrough: he was injured when a roll of paper fell on him at the cardboard box factory where he was working and awarded £1,000 compensation. It was 1968 and, short of winning the pools, this was as good as a windfall got. 'My dad couldn’t wait to get his hands on that money,' says Ian. 'He got the cheque and he didn’t even have a bank account to pay it into. He bought a static caravan by the sea and a two-up, two-down house for us in Hull.'

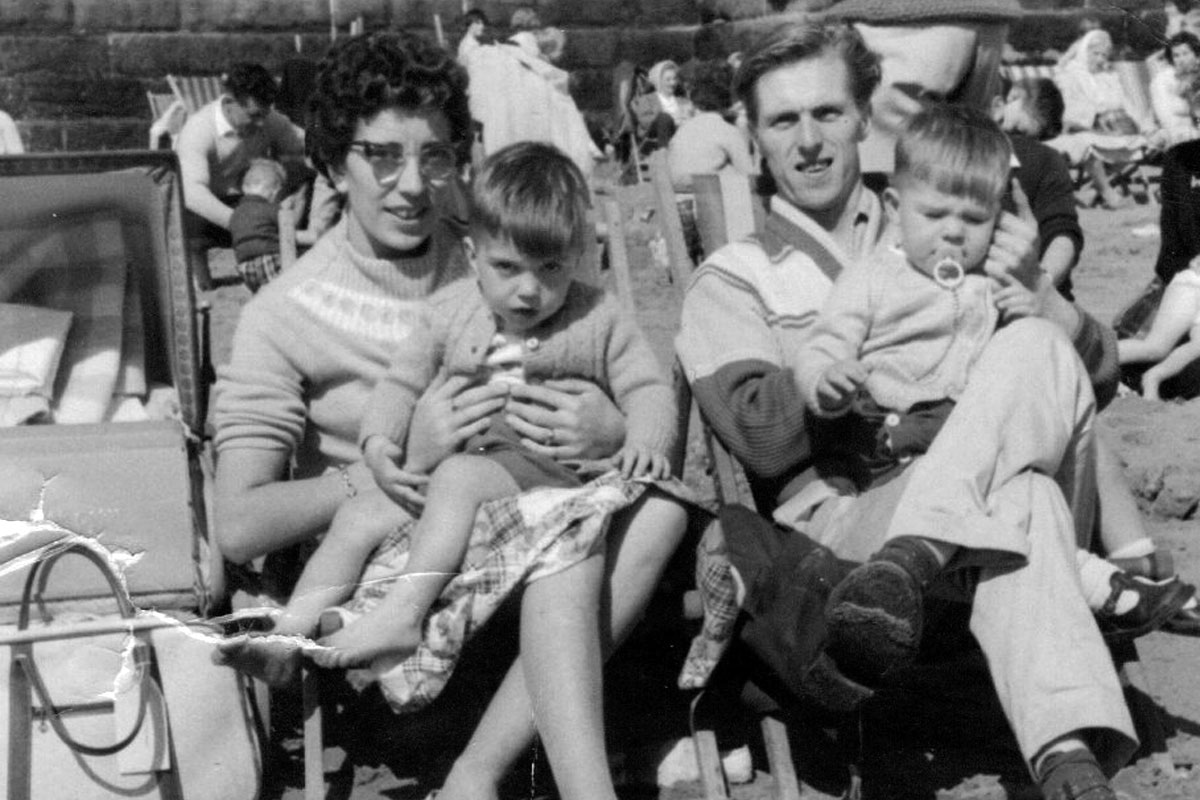

The family moved to Hull, but then Pauline had an affair with Sid’s brother, and the family split. Pauline’s bitterness over the way Sid had treated her through their marriage is evidenced in the fact that after the divorce she went through the photograph albums and cut Sid out of every image.

The Claytons, Sid and Pauline, with their sons Ian, Tony and Andrew. Pauline cut Sid’s face out of all the family pictures after the marriage ended.

Ian’s younger brothers stayed with their mother and uncle, but he went to live with his grandparents. It was a fortuitous turn of events: not only did his grandparents love and care about him in a way that his parents didn’t or couldn’t, but his grandfather became a substitute for the inadequate Sid. Ian clearly idolised him. 'He was a big, brave man’s man,' he says. 'He worked down the pit and had a reputation for hard drinking. He was a tough sort, there was no messing with him, no messing at all. But despite his rough exterior, when he held my gran to him, he had real tenderness; he was like a man holding a small bird.'

In the years that followed there was little contact with Sid, but many more father figures drifted in and out of Ian’s life: neighbours who seemed wise and kind, drinkers with interesting stories to share in the local pubs, sporting heroes he didn’t know but looked up to, even picture book heroes.

One father figure he became close to was fellow Yorkshireman Barry Hines, author of the bestselling book that became the 1969 Ken Loach film, Kes. 'I loved reading all my life, but as a boy Enid Blyton didn’t quite speak to me: I didn’t have an Uncle Quentin who owned an island,' says Ian. 'And then I read Barry, and here was the story of a boy whose mother spits on her shoes and polishes them on her way out to bingo. It was my world on the page and it changed the experience of literature for me.' Later, his career brought a meeting with Hines and the two became friends.

The notion of 'poetic sensibility' was what drew him to a substitute father. 'That’s what I love – it’s what I value. It’s what I’ve searched for all my life,' he says. He was captivated, time after time, by men who were astute, and witty and pithy and wise; all the things he wanted to be and had no role model for.

But then came the reunion with Sid. Father and son met only three times before Sid’s death in November 2013, but those meetings were enough to change Ian’s outlook on his dad. His book is littered with laugh-out-loud quips from Sid, whose wit seems unhampered by his encroaching cancer and increasingly bad hearing; like the point where Ian tells his father he’s off to China to do a lecturing tour. 'Bloody hell, lad!' says Sid. 'China! You’d think with all them people they’d have their own teachers there.'

Sid, it turns out, had a poetic sensibility all of his own. 'I searched for it all my life, and it wasn’t until the very end that I realised my dad had it all along,' says Ian.

And the truth, he also realised, was that, like most offspring, he was luckier than his father had been: life brought him more opportunities, more satisfaction and more love than it ever brought Sid. Now he’s gone, Ian is much softer about him than he used to be. 'What I reckon is that we all become the people our parents could never have been,' he says. 'We’re them, but we’re them moulded in another age.' He owed Sid more than he realised.