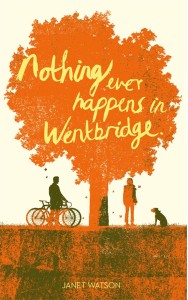

Janet Watson answers questions on her memoir Nothing Ever Happens in Wentbridge.

Q. Can you tell us a little bit about Nothing Ever Happens in Wentbridge?

A. I started writing Wentbridge while studying for a psychology degree. I would spend a few days away from my family each year before exam time and I was in a cosy farm cottage just outside Edinburgh, studying child development. I would learn notes on the topic of the day, then go for a wander in the fields, come back to reproduce the perfect child development essay, and find myself writing Wentbridge. Given what it’s about – growing up, first love, those intense late teen years when you believe no-one has ever felt the way you do, and when evenings are spent drinking too much and talking about the ‘meaning-of-life’ stuff you can’t believe anyone has ever thought or verbalised before you – I guess the child development course was a bit of a trigger for me.

While walking the dog the other morning, I realised that if I had to sum the book up in one word, I’d say it was about missing. Missing people, missing feelings and opportunities – a missing that never goes away but by writing it out, I have recognised and learned to live with. It’s about love and loss, but it’s not a ‘misery memoir’. A friend was reading it on the bus the other day and said she actually guffawed, out loud. Result!

Q. The scenes from 30 years ago are incredibly vivid, the use of diary extracts taking us right there. Were you a prolific diary keeper at that time and what was it like revisiting them after such a gap?

A. I was determined to use the diaries in the book as they were such a vital part in reconstructing the story, and in filling in some of the details that had wandered out of my memory somewhere along the way. My first diary was pink, and was a Princess Tina one. I think I started that in 1974 when I was just 10. Later, when I was 17 and 18, I needed at least a page a day and it was usually packed solid with tiny writing so that I could fit in as many details as possible. My diary was my confidante; somewhere I could relate all the stuff that I couldn’t tell my family and friends. It also felt important to record those rites-of-passage years. It was as though I somehow knew how I would need to look back on them one day, almost as proof of the amazing times with my friends. Revisiting the diaries was like coming home. They were funny and sad, and ridiculous and sometimes infuriating – for example when I had been a little too open and honest and then felt the need to scribble words out. I made such a good job of hiding words, and I knew some would have been useful for the book, but I couldn’t even guess them from the context. I sometimes wondered whether I should throw the diaries away as I grew older but something always made me hang on to them and I’m so glad I did.

Q. How was the experience of meeting up with old friends again, especially after such a deep immersion in the diaries?

A. In one respect I was nervous. The diaries had taken me back to my friends as they were in the Eighties, and the way we were, to quote the famous song. How would it be now, 25 years on? Yet there was also great curiosity and a desire to know them now, and find out what turns their lives had taken. Our first reunion was before I started writing the book, and that was so emotional. I felt I really needed to see everyone again after what happened in Jenny’s van – which is in the book – so I managed to find everyone and we arranged to get together for a weekend in Hull, meeting up in our old pub, the Duke, for the first time as a gang without Mark. It was wonderful to see everyone, but we all felt his loss so much by being back together. And I heard how the others had been deeply affected by Mark’s death too. I could share my feelings with them, and they understood. I wasn’t alone with it any more. When I started writing Wentbridge, I had a week away, travelling to the south coast first to talk to Gary and Adrian, then up to London and Mandy, then on to see Nick in Wiltshire, then Julie in West Yorkshire, and last but definitely not least, Tony and Sian near Hull. What was fascinating was comparing memories, and how they were both shared, but different, like looking at a film set from a different angle. And every last one of them was totally supportive of what I was doing in writing the memoir. I had been slightly worried about that – about them feeling that perhaps they didn’t want their party misdemeanours or teen romantic entanglements printed for all time in the pages of a book, but they all just said, ‘Don’t be daft Janbo.’

Q. How did it feel revisiting your time with Mark in such detail when writing the book?

A. It was the strangest thing but I would completely immerse myself in the past. Once the boys had gone to school, and the house was quiet, I would sit at the table with my laptop, thinking myself back into the feelings that went with what was written in the diaries, and etched in my memory. Between 9.30am and about 2.30pm, I wouldn’t move from my seat, so absorbed would I be in the past. I realised the only way to recreate my time with Mark was to relive it – particularly strange as a forty-something trying to imagine making love with Mark for the first time in the back of my old Austin! When the time came for me to get my head back into the present, and go and pick the boys up from school, I would literally have to drag myself back, realising at the same time that I was hungry and needed to go to the loo. I guess by reliving it in my imagination, it helped with the psychological process of honouring what Mark and I shared, and letting it go. And I tried really hard not to see him through rose-tinted specs. He was my first love, and naturally I thought he was gorgeous, but he wasn’t perfect, and I hope I managed to convey all aspects of him, and of how we were together.

Q. In the book you describe that after the ‘van thing’ it became imperative for you to write about Mark. How does it feel now that you’ve done that, and people are reading it?

A. Although I stopped writing in diaries back in the 1980s, I have always carried notebooks around with me, or kept one by the bed, as I find writing things ‘out of my mind’ really helps when it comes to finding solutions to problems, or just to find peace in the middle of a sleepless night. With ‘the van thing’ came a realisation of the extent to which I had denied my feelings for Mark and the need to write them out, if only to have somewhere to put them, if that makes sense? I guess writing the new ‘reality’ that had come up in my consciousness enabled me to relive my feelings and work through them, even without being able to talk to Mark about any of it. Getting the story out actually brought me an amazing sense of peace, and helped with an understanding of what lay in my own psychological foundations, so to speak – the trauma that had been at the root of some of the decisions I had taken in life, and how those decisions could never have turned out for the best. How could I love someone else when I hadn’t stopped loving Mark? The writing of it gave me an opportunity to revisit my subsequent relationships with a new perception.

How does it feel knowing people are reading it? Scary in one sense – I’m still waiting for someone to step out of the shadows and say: ‘You can’t feel like that, it’s not allowed.’ In another sense it’s exhilarating to have been so truthful about my story and know that is what people are reading now. I feel for Mark’s family in that the book will bring back trauma and loss for them – although they have been very understanding about the book which I told them about long before Route agreed to publish it. I’m slightly nervous about my children reading what I ‘got up to’ at the ages they are now, and very grateful to my dad for whom it has been one hell of an eye opener! He has been brilliant, understanding and thoughtful from the moment I placed the manuscript in his hands.

On the whole, I feel very proud of the story, and hope readers will be able to know who Mark was. And I’m getting lots of positive feedback from people who are relating to the feelings and events in a way which, they say, has helped them to a greater understanding of their own situations, which feels fantastic.