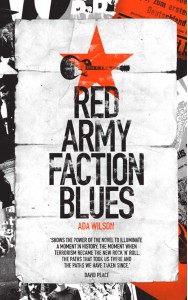

Ada Wilson interviewed about his novel Red Army Faction Blues. Conducted at the time of publication in 2012.

Q. What was the genesis of Red Army Faction Blues?

Football and rock music are the cultural glue for many people, myself included, but I’d never read a compelling piece of fiction about either, really, and was somewhat at a loss to explain why. Until The Damned United. Besides being terrific, I found it both shocking and liberating in what it suggested in terms of potential subject matter and how to shine a new light on the immediate past. It’s about football, but at the same time, not at all. It’s about a real person, a well-known celebrity, turned symbol or cipher. Much of modern culture, for a number of reasons, appears to have been closed off to imaginative fiction and I think there is a hunger for alternatives to ‘official’ versions. I was already corresponding with David Peace a little, and I’d mentioned the story of the first incarnation of Fleetwood Mac, how the band’s initial disintegration had assumed mythical status – become another symbol really, for the end of 1960s optimism and experimentation. In particular, what the surviving members of Fleetwood Mac in interviews referred to as ‘The Munich Horrorshow’, which they attributed to the start of the sad decline of Peter Green, the band’s original creative force. I initially tried to make Green the protagonist, but it was hopeless – the known facts forced out any freedom and the clichés flowed!

Q. What was the source of your fascination with Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac?

As a kid I was a big fan of Peter Green and one of the first albums I ever owned was The Pious Bird of Good Omen – the one with the nun holding an albatross on the front. When I started to learn to play guitar it was Green I initially tried to copy. Perhaps because it seemed simple – deceptively so, of course. With hindsight, they were a very effective singles band, while never quite making the classic album they threatened to. But that run of singles – ‘Need Your Love So Bad’, ‘Black Magic Woman’, ‘Albatross’ ‘Man of the World’, ‘Oh Well’ and ‘Green Manalishi’ – is quite staggering in its breadth and originality. And then of course, what happened to the three guitarists is awfully tragic – even as Fleetwood Mac went on to being the best-selling band of the 1970s. The 60s ended when I was ten, so the story was initially skewed through the prism of childhood for me, when the generation above me all seemed to be speaking in magical and exciting codes I had only a very limited understanding of.

Q. How did the connection between Peter Green and the political activity in Berlin open up to you?

I first found a clip in a German celebrity magazine – about antique cars, of all things – in which Rainer Langhans first spoke about meeting Peter Green at Munich Airport, and the guitarist’s visit to the High Fish Commune. The anecdote has subsequently been bandied around internet chat sites. At that point, Langhans was someone I instantly recognised as this media icon from the 1960s, but I can’t say I was that familiar with the whole saga of Kommune 1. Political action and music were so tightly entwined for a while, and then there was the whole hippy thing of ‘the journey’ – of self exploration and expanded consciousness which sounds rather laughable now. Total freedom – whatever that may be – is what both Kommune 1 and Peter Green thought they were pursuing on their own ‘journeys’. They went about it recklessly, and as we know, it didn’t end so well. The very differing conception of what the 1960s represented to that generation in England and Germany was another thing I was seeking to draw out

Q. Little is known of Kommune 1 outside of Germany, what can you tell us about them?

K1 was a group of Berlin-based students who came together to explore the idea of living in a different way, inspired by the anti-consumerist doctrines of writers like Marcuse, and also by the Situationists. One of the left-wing theories floating around at the time was that the smallest cell of the state was the nuclear family, and it was this that had to be smashed if history wasn’t to repeat itself. It was very much a reaction to the terrible legacy of their parents’ generation and fascism. K1 attracted almost instant notoriety for an alleged assassination attempt on the visiting vice-president of the United States – which turned out to have involved custard pies and flour bombs. It became all about political ‘actions’, demonstrations for a time – the most notable being what’s acknowledged as the turning point of the German student movement, when the unarmed Benno Ohnesorg was shot by a police officer called Kurras (who much later turned out to be an informer for the East German Stasi). Satire and provocation though, was what K1 excelled at, particularly Langhans and Fritz Teufel.Their perceived lack of seriousness, however, alienated many, and the commune was eventually expelled from the high-minded German student’s movement, the SDS.

Tensions arose between K1 over the direction it should take, and eventually Langhans came more to the fore and was surrounding himself with beautiful people, most notably the model Uschi Obermaier. The rest of the original communards became ostracised and there was a lot of jealousy, especially after Langhans declared the intention was to make a lot of money by doing very little – being famous for just being famous – a very 21st Century concept, more Simon Cowell than Che Guevara. It worked too, for a while – Langhans and Obermaier became a kind of German John and Yoko. But the circumstances leading up to their leaving Berlin for Munich – in order to make that mythical meeting with Peter Green a few months later – are incredibly shocking, and a pivotal part of my book, so I’ll say no more here.

Today, Langhans is probably as famous now as he’s ever been, having last year appeared in the German version of I’m a Celebrity, Get me out of Here! – spending a night in a coffin filled with maggots at the grand old age of 71. Nothing much fazes him.

Q. How much research was involved with the book and how did you approach it?

It’s interesting, but I don’t think this book could have been written pre-internet. Some of the channels just weren’t open. The ability to source what’s there in a click, and connect with people who may know other things in two clicks and a sentence. This is of course, a fairly recent method of gathering information. And my German language skills are rudimentary. I understand much more than I’d be confident to attempt speaking – the typical British paralysis, probably. I can do taxis and hotels, and bond after a pint or two. But with Google Translate, for instance, I can manage much more. Although it’s a different sort of reading – not in a straight line at all – like you’re pulling the key words you don’t quite get out of a sentence and then imposing an order on the sentences. Another very internet type of activity. So the truth you’re going to arrive at will be different to that in the past, but probably no less relevant. The New Currency of Communication.

There’s a wonderful novel by Francis Spufford called Red Plenty. It’s about the economic system in Stalin’s Russia, but don’t let that put you off. It’s not about that, really. It’s about the hopes and aspirations of many very interesting people over the past century. It’s utterly wonderful, and pure fiction in this new way. Maybe the term ‘speculative fiction’ should now be applied to the past, rather than the way it was once intended, about the future? What does that imply? At the end of that book, Spufford fesses up to being unable to read a word of Russian. So in a way, he was only getting what was available already in translation too. But as a result of the internet, this is much greater, yet only a fraction of what could be researched in libraries, with time and patience. And financial resources. I probably went a bit further, in razoring apart entire German page texts that I couldn’t get via the internet and feeding them through the scanner and then into Google Translate. The research got a bit like panning for gold, I guess.

Meeting Rainer Langhans and Christa Ritter, who’s the archivist for all the Kommune 1 stuff, was equally illuminating, and as frustrating in a different way. Their versions were what I already had. They couldn’t tell me about the texture of a table, the colour of a cigarette packet, the smell of a street scene in 1967. That was down to imagination. It made me realise there wasn’t even any point in approaching anybody to do with Fleetwood Mac, that story being even more layered in the retelling – and buffered by an entire industry propagating the ‘official’ version. If the past is, as has been said, ‘another country’, then it’s already over-populated with ‘official’ guides. The interest, as always, is in ducking down the side lanes, yesterday, today, or tomorrow.

Q. The narrator of Red Army Faction Blues, Peter Urbach, was an agent provocateur who infiltrated Kommune 1. What can you tell us about him?

He’s real, just like Brian Clough. My symbol and cipher.

He came from Poland, apparently, and he didn’t fit in from the start, which just goes to show how pure the intentions were, how trusting and idealistic these people were, at the start. He was married with kids – the epitome of that nuclear family K1 was so opposed to. And very working class, with a job – or at least a cover – on the East German-run railway service that ran through West Berlin at the time. But the rich, well-educated members of K1 were in thrall to a genuine prole. Especially such a charismatic one, who could make things happen.

It’s quite curious – the more I researched and got my sequence of events straight, the more Peter Urbach kept pushing himself forward. He was everywhere: taking care of practical things and chivvying along the subversion at Kommune 1; putting the earliest bombs in the backpack of SDS leader Rudi Dutschke; driving Fritz Teufel and Bommi Baumann around Berlin with a van full of molotov cocktails, in search of the villa of newspaper magnate Springer; turning up outside the intellectual Republican Club with a case full of grenades. Later, shooting up Dieter Kunzelmann and many more with cheap heroin and having Andy Baader and the disgraced lawyer Horst Mahler – the key figures in the development of what quickly became the demented and dangerous Red Army Faction/Baader-Meinhof Gang – dig up cemetery plots in a vain search for a cache of WW2 pistols. To name but a few of his wheezes. And then, all of a sudden he turns up as a key prosecution witness for the West German government in the first Red Army Faction trial, of Horst Mahler alone, in 1971. But his testimony is rubbished, and he subsequently disappears forever. I like to think that much of that spirit of the times – Imagination is seizing power – rubbed off tremendously on him too. He wouldn’t have done what he did otherwise. Wherever he might be. It’s strange too, that as I was finalising this book, the stories of Mark Kennedy and other police officers who’d been put under deep cover to infiltrate left-wing protest groups in the UK were unravelling. What on earth could have been the reasoning there?

Q. What lessons can the young people of today draw from the book?

I think what might be striking to some younger readers is the fact that among the intelligentsia of West Berlin and elsewhere there was already so much anti-capitalist sentiment and abhorrence of materialism. This was almost fifty years ago, and it hadn’t even started! There was no McDonald’s or anything resembling it, the brands had yet to take any kind of hold, television and even central heating had yet to become common. It was only a few years after rationing in Britain and most of Berlin was still a bombsite. Yet there was this resistance; a recognition of the shallow rewards being offered. Was it Luddite? Hardly.

There was fierce opposition to the manipulation and excesses of the press too, and particularly newspaper baron Springer. Multiply those manipulations and excesses by a million and you’re somewhere near to where we are now. Most important of all though, is the feeling of connectivity and the potential for positive change that existed. Kommune 1 and the greater student movement in Berlin and West Germany knew that what they were being sold wasn’t good enough. They quickly became adept at reading between the lines, and long before the internet, were opening up channels to counter the attempts of the powerful to exercise even tighter control over the many. The daring and originality of much what happened back then should be inspiring. But everyone knows much more now – and not just those seeking change, but the small minority unwilling to share too. They really have the power to make the world fantastic, for everyone, without giving up very much at all. People like Bill Gates have to be lauded for recognising this. I really wish the rest would consider it soon, before it ends in tears again.