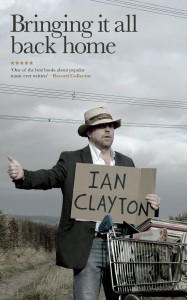

Interview with Ian Clayton about his memoir Bringing It All Back Home, conducted at the time of publication in 2006.

Can you tell us a little bit about why you wanted to write this book?

It’s just some stories that I’ve been telling for years and never written down. Most stories circulate in their own neighbourhood, you might call this a gang of stories bursting out of where they are from.

The book is essentially about music, but in it you do talk a lot about the value of the stories and the power of storytelling.

It starts with sounds really. If you enjoy music it’s because you’ve enjoyed sounds as a kid. The sounds can be anything, from listening to birds whistling in the morning to listening to the sounds of the street where you live, to listening to arguments. In my case I listened to a lot of arguments because I grew up in a house full of them. I listened to what people were shouting to each other about. And it’s a learning thing then. Because I tried to understand what the arguments were about and in trying to understand what arguments are about I get an understanding of what people are about. So that’s the first part of it, listening to sounds, listening to noises. I always enjoyed listening to what was going on, it could be my old granddad telling stories, could be old neighbours telling ancient stories about what their lives were about and what entertained them.

I listened to a lot of radio when I was a kid, so that’s a really big memory for me. Radio Luxemburg in my case, sometimes the pirate radio stations I got to hear. The few records that we had I enjoyed and on top of that are the stories that children tell each other at schools and I always got something out of that; playground games, rhymes, songs that kids were singing in playgrounds, stories that kids were telling in playgrounds.

Then above that I grew up in a place where Working Men’s Clubs were strong and they always had entertainment at weekends and I’d hear songs coming out of those places. These songs were contemporary in a way because the songs that turns were singing in working men’s clubs were up to date, but also old fashioned because they were presented in a way that entertainment to working people had been presented for a hundred years, right back to the music halls. And although I didn’t know it when I was a kid, thirty years later I would become fascinated by music hall and I think the fascination is because that was the music I was hearing as a kid. The songs that my relatives and friends and neighbours were singing coming out of working men’s clubs wasn’t much different to what people had been listening to for a hundred years or more. So that’s the starting point really. The starting point isn’t pop music, rock music or folk music or any kind of music, it’s sounds; sounds of my neighbourhood, my street, my school playground, my family home and places of entertainment, which was working men’s clubs.

You’re saying that fascination with stories and the fascination with music is inseparable. So your pursuit of music which is outlined in this book, is that a pursuit of stories and other places?

I can’t separate anything, I never have been able to. It’s what is usually wrapped up as culture by better educated, more culturally aware people. They will say that conversation, music, art, creativity, reading, stories, dance, however we choose to express ourselves creatively, is culture. I never got the opportunity to see anything beyond the confines of my town where I lived until I was a young man, so for the first sixteen years of my life my culture was wrapped up in my environment and what that means. So anything that is coming to me is synthesised really. If I hear a record that is on Radio One, I don’t hear it on Radio One, I hear it in my kitchen on a wireless. And so it means something because of that. Therefore when I hear The Kinks singing ‘Lola’, I don’t think of it as a band that is recording in London as part of a 1960s, early 1970s pop culture, I hear it as part of an everyday occurrence coming from a wireless or a record in my house. I don’t recognise the pop music industry as a separate entity to my everyday life, it’s just another part of what I’m listening to or experiencing. To be precise when I think of ‘Lola’ it makes me recall a caravan holiday at Withernsea on the Yorkshire coast, which is a long way from ‘old Soho where they drink champagne and it tastes just like cherry cola.’

There are many journeys in the book, lots of starting points that lead you to other stories; finding a blues record in a second hand shop in Cornwall leads you to Bessie Smith’s deathbed; listening to the wireless leads on to you being on the wireless, to making radio. Have you educated yourself through these things?

It’s utilising experience. I didn’t think this when I was younger, I’m not even sure I’m completely aware of what I’m doing now, but I think that if the metaphor for life is the journey, then part of that metaphor is experiences. If life’s journey is about experiences that you have in life, then it necessarily follows that one experience must lead to another and that if you can enjoy and learn from those experiences then your natural and instinctive inquisitiveness leads you from one experience to the next. I don’t have any qualms about making the leap from the general hubbub of noise in my backyard to the concert hall where I go to see my first opera.

The world is awash with music and we get it pumped at us on a regular basis. How do you discern, what is it that interests you in a piece of music? How do you make your steps?

You’re touching on taste there. I think authenticity is the word. If with expression – whether it be musical, storytelling or however you choose to express yourself – if you are doing that with sincerity then it necessarily follows that it is an authentic experience of who you are, where you are from, what you are aiming towards and what you are trying to understand in order to transfer that understanding to somebody else. If you take an old music hall song that my granddad used to sing, I think that’s a great thing because it’s the popular music of that time and it’s meant something to his life and therefore meant something to mine because I’m part of him. If you take a Blue Note jazz record by Ike Quebec or Art Blakey it’s completely out of my experience in real terms but I can see what they are doing, expressing something which is dear to them or near to them, so that’s important. I’ve listened to African music, I’ve never been to West Africa or Central Africa, but I enjoy the music of Congo and Mali because I can see what they are doing, that they are expressing something which is close to them, meaningful and authentic.

As you’ve travelled through your life and you’ve made journeys and connections, as you’ve moved from one thing to another there is a sense in the book of collecting and hoarding as you go along and you fill your house. There is this talk of your ‘head being your house and your house being your head’. What is this instinct about? You may hear the hubbub of a playground, but that is a transient and passes by, why is it you feel the need to collect music and artefacts?

I think it might be primitive. Most human beings who have nothing try to acquire and once they’ve acquired they try to keep. Here again I don’t separate the collections in my house from the collections in my head. Playground hubbub is transient, but even though it doesn’t sit on a shelf in my house it is filed somewhere in my head. I don’t want to make a big sociological argument for this book, but I think working class people like to acquire things that they haven’t got and they hold them. My record collection is pristine and I don’t want to hurt it, I want it be as good as it was when I got it. There is a passage in this book that is very important to me and that is when I was a little boy I liked to collect things because I didn’t want them to be lost. I used to collect things that were washed up from the sea at the seaside because it seemed to me they were very lonely, pieces of wood with bits of writing on that were once crates for fruit or vegetables, once were boxes that had things in them and now were destroyed and tossed about on the waters. I saved stuff like that because it seemed to me that it was more important to render them not lost. I don’t know if that connects. I think it probably does actually, if you render something not lost anymore it connects to something that’s been created, so something that’s found is as important as something that is made. I’ve been thinking about this a lot in the last few years, while creativity is a good thing for all human beings to be involved in – and I have been involved in a lot of creativity in my life – I think that finding things is just as important and what you can do with things that you find is great.

There are lots of references in the book to your desire as a young man to make maps. You had this very early, almost romantic fascination about foreign places and wanting to create maps. Is your library and record collection and your trinkets some kind of map of your life?

Yes they are, they are places on a map, it’s a progressive route. I also think that I’m very romantically and sentimentally attached to my hometown and I want it to be as important as other people’s hometowns. I’ve been upset over the years that there are certain northern English working class towns that don’t get the recognition that they deserve. I’ve sophisticated this idea over the years – I didn’t know this when I started to think about it – but it seems to me that my hometown is as important as anybody else’s hometown anywhere in the world. So, if I can find something from another place and compare it to something that’s from where I’m from and share the comparisons and draw the significances, then it lifts my hometown up to their level, or the level that they perceive themselves to be at. It’s a way of drawing maps and drawing lines between places. This is what I’ve heard from your place, now listen to something coming from mine.

The title Bringing It All Back Home is in many ways about a dialogue. Exactly what you have just described, a dialogue between what you have, what you can bring to it and what you can export as well.

I don’t think there is any point in making any journey whatsoever if you are not going to take anything with you as well as bring something back. I despise the idea of being a cultural tourist; I don’t want to be one. That means to say that the only thing you will ever do is go to somewhere to see what you can get from it. I’d rather take something with me and then it works both ways.

If this book represents your journey so far, where do you go from here? What is interesting you now, what musical journeys do you expect to embark on?

I’ll carry on doing what I do. It’s undefined. We talk about maps, we talk about compass directions, we talk about journeys, and journeys always suggest that there is a start and a middle bit and that you come to some kind of end. This book doesn’t work in that way because it goes round and round. Time isn’t accounted for, geographical location isn’t accounted for, except to say that there are certain places and comparisons that I have made. I think that there are towns in America and Eastern Europe and Asia that have got more in common with where I’m from than places in the south of this country.

The hardest thing of all to deal with has been the terrible family tragedy that befell us. As I was coming to the end of this book my daughter Billie died in a canoeing accident. My partner Heather encouraged me to write about this and include it in the book. Billie’s death has ended many journeys for me. A lot of my life now, both professionally and personally, is going to be trying to work out how to restart the journey. I don’t want to make a big thing about it, but it just seems that a lot of endings have come all at the same time; working on a book that’s finished, having a child in your family that has died, doing some cathartic thing like getting a lot of stories out of you means that they’re not in you anymore. There’s a lot of endings that have come all at once.

On the idea of time and how things connect to each other across all different sorts of levels, there’s a section in the book called ‘A Seed Doesn’t Stay in the Ground Forever’, do you see that there are seeds in the book that are part of that continuum, is there stuff in there that you will relate to and bring round again?

Of course there is. Nothing ever ends in that sense. There are resonances in this book coming from hundreds of years ago, which means that there will be echoes in years to come. It’s finding that ear for both resonance and echo and I’ll do it. At the moment I’m a bit lost with that, I’m not quite sure what a lot of things mean anymore and I’m not sure what is going to be important anymore. I’ll just find it, it’ll happen. I’ve never planned, it’s always been quite an anarchic journey, sometimes I think the harder I try to make the maps the more I throw them away.